abc Berlin 2012

Clemens von Wedemeyer

Sep 13–16, 2012

Sep 13–16, 2012

Installation documenting Wedemeyer's Open Air Cinema project for the City of Mardin, Turkey, in 2011

In the context of “My City“ five artists have been invited to develop unique projects, each for a different city in Turkey. Clemens von Wedemeyer has developed a sculptural openair cinema at the border of the old city of Mardin, overlooking the Mesopotamian plain. hereas the front of Wedemeyers‘ double sided screen construction serves for film projections at night, the back of the screen functions as a mirror, reflecting the afternoon sun down to valley. Wedemeyers‘ own film about the sun and the city of Mardin will be among the first films to be shown at this new venue.

Clemens von Wedemeyer wrote about his project:

Due to its once religiously diverse and multilingual (Arabic, Kurdish, Turkish, Aramaic…) population, the city of Mardin in southeastern Turkey is sometimes called “Little Jerusalem”. During recent decades, however, the region has been marred by the Turkish-Kurdish Conflict.

After about 25 years without a functioning movie theater, it was only last year that one, managed by a local cinema association, was reopened in Mardin’s old city. Every September, a film festival takes place. Visitors are more likely to attend when the screenings take place outdoors.

In an art project initiated by the British Council and in cooperation with architects from Istanbul, I designed an open-air cinema (to be run by the cinema association) for Mardin. For a long time I searched for an ideal site, a new, permanent location, specifically for the open-air cinema. I wanted it to be lodged between the city and the Mesopotamian plains below. Finally we found the spot: below the 16th century Koran school Kasimyie Medrese, on the western edge of the city directly above a ridge. It lies about a kilometer from the old town with, immediately behind the screen, the beginnings of the open landscape of the plains.

For me it was about creating an open (and opened) cinema, meaning one that could be experienced by many and, at the same time, in which the formal principles of cinema would become visible. “Sun Cinema” is composed of three parts: a free standing screen, an amphitheater, and the projector’s triangular base. The triangle symbolizes the beams of light of the projector. I also wanted to draw a connection between the cinema and the sun: in the morning the first rays of sunlight strike the front of the 6°—12 meter screen, at which time one could enact a shadow play using one’s own body. In the evening, the setting sun is reflected back to the south by metallic mirror panels that cover the backside of the screen.

The sun as illuminator: This sun imagery refers to studies of light in ancient Arabia, which were concurrent with investigations of the human eye. In his book Florence and Baghdad: a West-Eastern History of Seeing, Hans Belting writes that investigations of the eye and the sun made by Arabian scientists in the Middle Ages led to the introduction of perspective in Western Europe during the Renaissance. Even older ties of this region to the sun are evidenced by solar cults and religions, which focus on sun and fire (Yezidi, Semsi, Zoroastrianism, etc.). In Mardin a room with a window facing the East was found under an ancient Aramaic cloister. Presumably, it had been used by sun or fire worshippers, such as the Zoroastrians. Tour guides present the room as a curiosity. Today, the local Christian and Moslem inhabitants might view these solar cults as heretical, yet aspects of these could have been integrated into these religions, for instance the eternal flame or the Ramadan tradition of fasting in rhythm with the sun’s visibility.

Cinema was preceded by shadow plays and the camera obscura before taking over as the dominant art form utilizing the absorption and projection of light. Alexander Kluge describes another connection between the sun and cinema in his book Geschichten vom Kino with the idea of a cosmic, universal cinema (“Kosmischen Universalkino”). He traces this concept back to an 1846 publication by the lawyer Felix Eberty, The Stars and the Earth. Kluge writes, "Eberty (…) rightly assumed, that a ray of light which left the earth on Good Frida in the year 30 A.D. continues to move out into the cosmos and away from us. Therefore the entirety of history is preserved in the path of light. The entire history of the world is therefore crossing the cosmos in the form of moving pictures (Eberty himself had never heard the term cinema).” Behind the screen one sees oneself. Not only does the rear side of the screen mirror the sun, but one can see in it one’s own reflection. Other people’s films are shown on the screen’s front, but when one makes a step behind the screen during the day, one can view one’s mirror image in the landscape or the sun reflecting off one’s skin and clothing.

In addition to the cinema building project, I shot a film about the city Mardin and the search for the site for the new cinema: Light&Space;, 45 min, 2010. The design of the open-air cinema was discussed with architecture students from the Technical University of Istanbul and realized together with the architect Gürden Gür.

Clemens von Wedemeyer: Sun Cinema project

Sun Cinema Location, 2011

HD, Blue Ray, colour, stereo sound

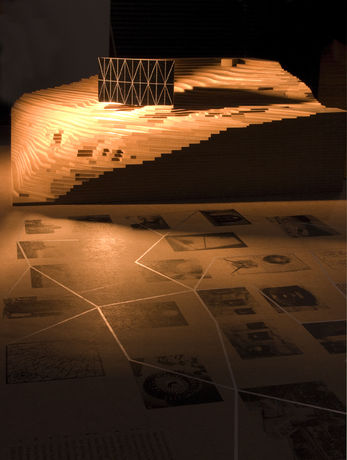

Sun Cinema Model, 2011

MDF, stainless steel

25 x 65 x 65 cm

Research Poster, 2011

pencil on black and white Xerox print

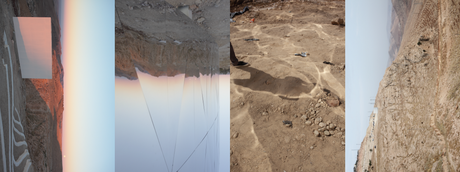

Early Morning I, 2011

c-print glued on PVC

30 x 45 cm

Early Morning II, 2011

c-print glued on PVC

30 x 45 cm

Early Morning III, 2011

c-print glued on PVC

30 x 45 cm

Early Morning IV, 2011

c-print glued on PVC

30 x 45 cm

Reflections, 2011

c-print

series of 5 c-print, 75 x 50 cm each

First Day, 2011

c-print glued on PVC

series of 8 c-print, 30 x 45 cm each