Jun 26–Jul 31, 2016

With Djonga Bismar & Manenga Kibwila / CATPC / IHA / Renzo Martens, Chto Delat, Heinrich Dunst, Alice Creischer, Eugenio Dittborn, Barbara Hammer, Ramon Haze, Hiwa K, Chris Martin, Dierk Schmidt, Frédéric Moser & Philippe Schwinger, Mario Pfeifer, Tina Schulz, Michael E. Smith, Franz Erhard Walther, Clemens von Wedemeyer, Tobias Zielony

Most art stays in the dark. It slumbers in storage, rests in graphic-art cabinets, enjoys the climate-controlled environment in free port warehouses and museum basements, or catches dust up in the attic. Now and then a few pieces come to light, but what feels like 90 percent of the art in public and private collections is under lock and key, most of it permanently. KOW is no exception to the rule, though the art we keep at three locations and stored on numerous hard drives shouldn’t actually be there. It’s not ours—it belongs to the artists, and we’d all prefer to see it go sooner rather than later. But for the time being it’s sitting on shelves and waiting: leftover display pieces and unsold art-fair exhibits, studio works and biennial projects and many a challenging aesthetic production in wooden crates and cardboard boxes, in portfolios and folders, hoping, with us, for better days. Some of them circulate in exhibitions and then return into our care. Galleries are in no small part lending operations and logistics agencies.

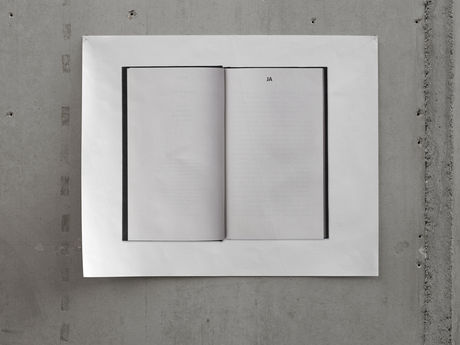

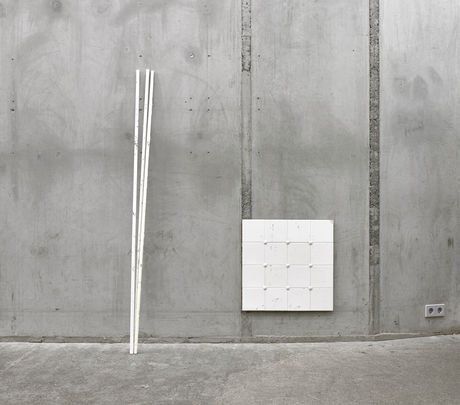

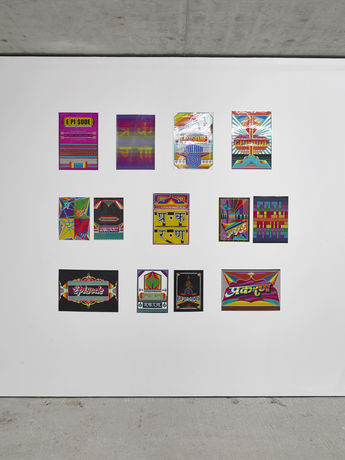

Now we’ve prepared a special treat for ourselves: this summer, we’re bringing some beloved works we store and manage to light. Among them are objects by the artist group Ramon Haze, which, to our minds, was one of the most significant positions in Leipzig in the 1990s and is largely forgotten today. In a future in which art is unknown, the collector-detective Ramon Haze reconstructs fragments of the twentieth century’s art history—and makes a bit of a mess of it. For example, he classifies Andreas Baader’s bucket bombs and kitchen tiles by the obscure Ruth Tauer as eminent works from the past on a par with Jeff Koons’s floating basketballs: three pieces from Haze’s archival collection, which at one time took up several factory halls. In the 1960s, Franz Erhard Walther started thinking of being kept in storage as no less valid a condition for his objects (usually made of fabric) than being staged or used. Folded and packed up or laid out and in action: as Walther sees it, these are merely different phases that his open-ended conception of the work passes through. Most art, however, is different—put it away and it’s effectively gone.

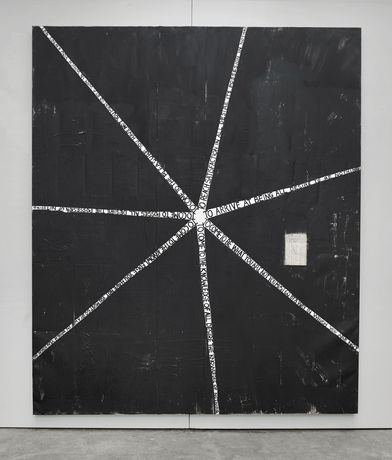

Behind the wooden slats of crates and layers of bubble wrap looms the dark realm of aesthetic inertia. It's a classical quandary of art theory: was the Venus de Milo a work of art during all the centuries it spent underground? Potentially: yes. De facto: no. Beginning in the mid-1980s, Chris Martin’s studio in Brooklyn filled up with hundreds of paintings, mostly in large formats, and eventually swelled into an enormous magazine only a few pictures managed to escape. It wasn’t until about a decade ago, when Martin’s art attracted international interest, that his stock started to thin out. We present “St. John of the Cross,” a major work from the 1990s, which has been parked at KOW since Martin’s retrospective at Kunsthalle Düsseldorf in 2011. In the case of Eugenio Dittborn, it was the geographical and cultural isolation of Chile under the Pinochet dictatorship that prevented his work from reaching a wider public audience, and so, from 1986 on, he participated in the international exhibition circuit by mailing his paintings on folded fabric panels—he dubbed them pinturas aeropostales—to addressees abroad.

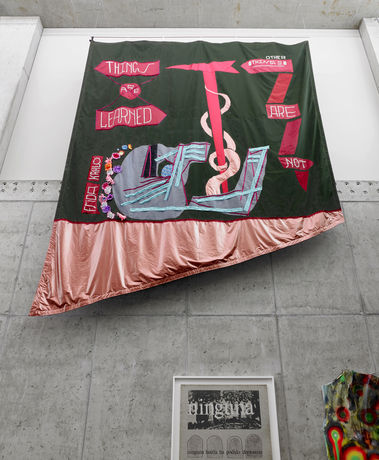

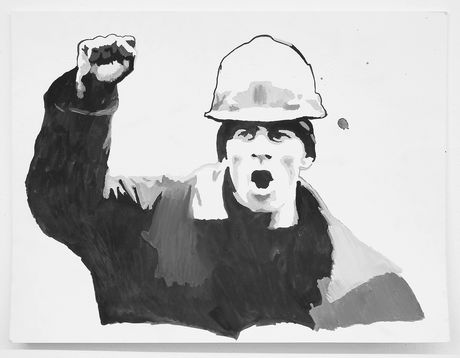

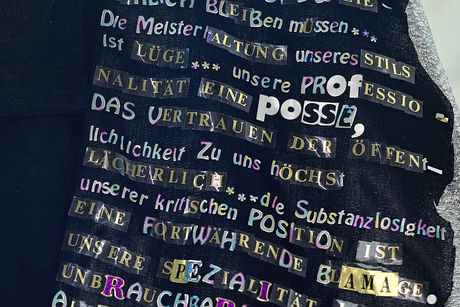

More recently, Renzo Martens has relied on the Internet to bring the heavy clay sculptures created by the Congolese Plantation Workers Art League to Europe: instead of going to the trouble of arranging for shipment from the Congo, he sends 3D data sets to Holland, where the works are replicated in chocolate so they can be fed into the Western art market . “Why did I go into debt?” Dierk Schmidt asks in 1997; Alice Creischer’s Show Master Jacket (1999) is a caustically funny comment on the profit expectations that fuel the gallery business. In 2004, the Museum der bildenden Künste in Leipzig features in Clemens von Wedemeyer’s dramatic production of the art museum–as–homeless shelter. Barbara Hammer’s photographs documenting the feminist guerrilla actions she staged in empty museum halls in 1972 sat in her studio for four decades, unseen by anyone. Also on display are early videos by Frédéric Moser & Philippe Schwinger and selections from the expansive multipart installations of the Russian collective Chto Delat, plus works by Heinrich Dunst, Hiwa K, Mario Pfeifer, Tina Schulz, Michael E. Smith, and Tobias Zielony.

The exhibition opens with KOW’s summer party on June 25—stop by and join us in celebrating the artists and their work.

Translation: Gerrit Jackson

Dossier: