Sep 13–Nov 23, 2014

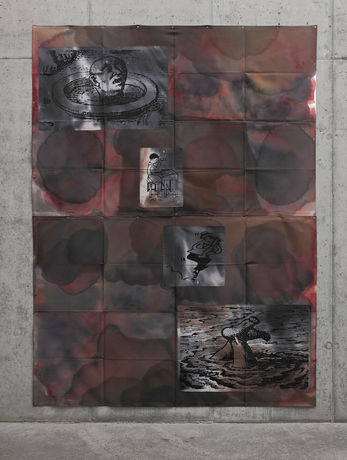

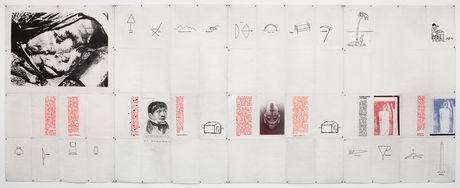

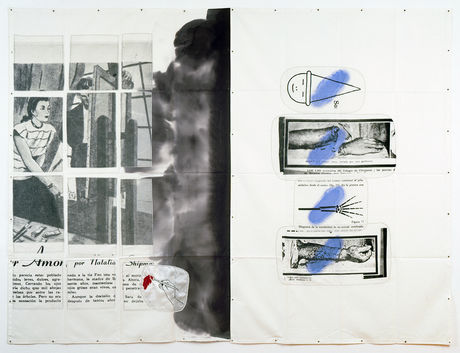

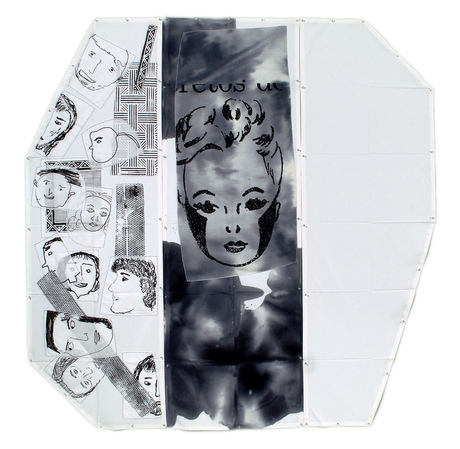

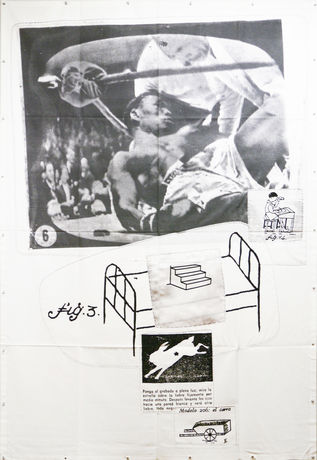

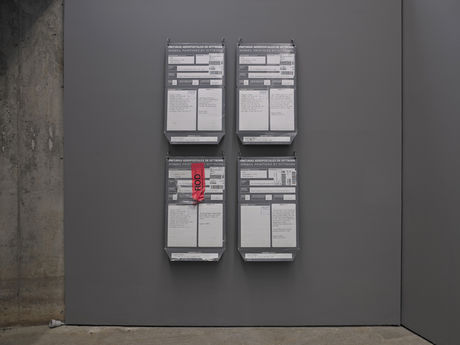

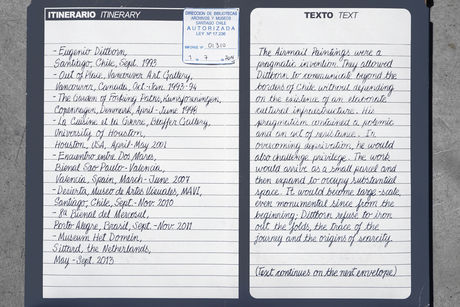

Over the past weeks, we received almost fifty letters from Santiago de Chile. Their content: around 1,600 square feet of fabric, folded up and squeezed into mailing envelopes—the pieces of twelve works Eugenio Dittborn created between 1986 and 2014. Pinturas Aeropostales: Airmail Paintings. Pictures made to travel the world by airmail from Chile that have now arrived for a stopover in Berlin. Paintings, silkscreen prints, and textile collages, each on a 32-square-foot panel of cotton, felt, or sometimes paper, that we pull from the envelopes, unfold, and assemble on our walls. The monographic survey of the oeuvre of the Chilean artist, who was born in 1943, will be his first solo show at a gallery in Europe.

At any given moment, innumerable pictures are on their way around the globe, in analogue or digital formats, and many of them are packed up somewhere and unpacked somewhere else. In Dittborn’s work, however, traveling is immanent to the art. Circulation is its purpose, being wrapped up and shipped defines its formal structure, and it continually connects signs, times, and people, only to separate them again. The entire oeuvre is a permanent state of transit. Beginning in 1986, Dittborn used the international postal system to escape the geographical and cultural isolation of Chile under Pinochet’s dictatorship and participate in the global exhibition circuit. Since that time, his letters have reached museums and biennials like boomerangs that unfold into pictures in sometimes monumental formats and then fly back to Santiago. Each exhibition of Dittborn’s work is a moment of rest for a work whose form lies in its intrinsic restlessness.

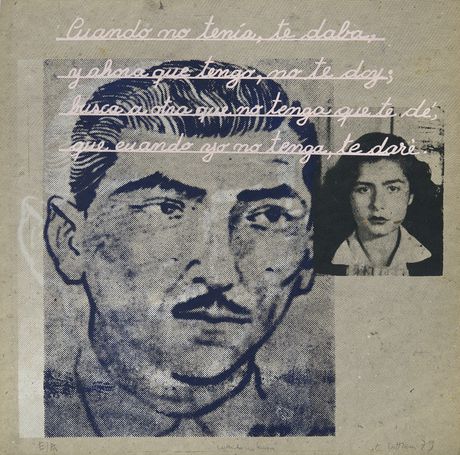

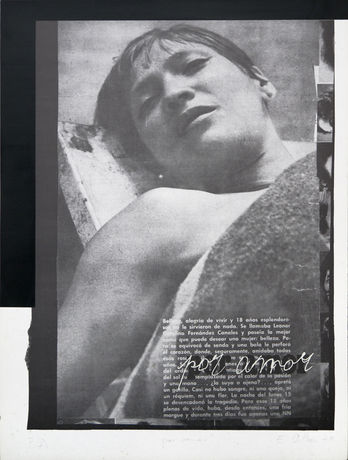

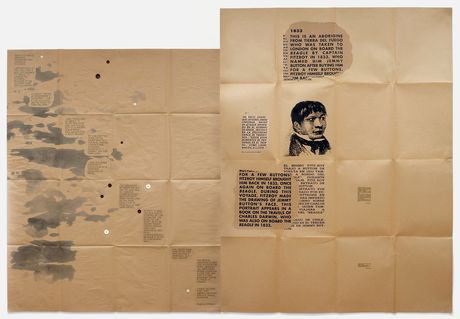

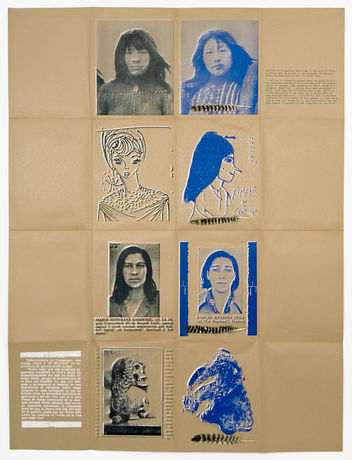

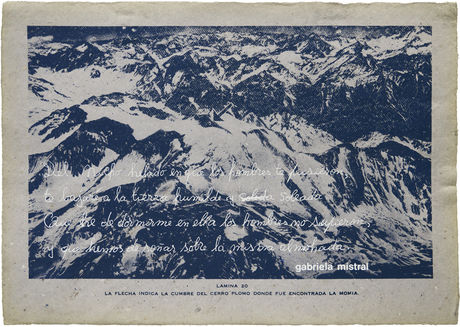

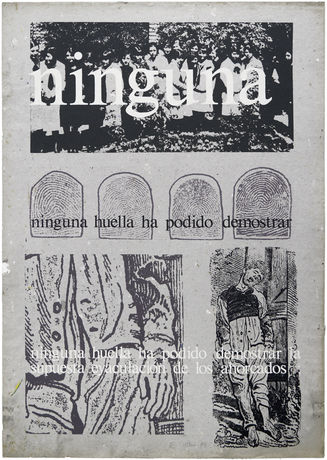

If we seize that moment’s opportunity and read the mail that has come in, a second movement commences: Dittborn mobilizes historic sources and lets their echoes sweep his panels of fabric, to be refracted by their physical substance and semiotic inventory. Time and again, Chile’s past has been subject to confiscations. The Spanish conquistadores, the Pinochet regime, and the post-despotic culture of amnesia effaced recollections and individuals from the varying narrative templates they imposed on the country and its people. Dittborn uses serigraphy to bring back texts and images from newspapers and books of the past decades, recirculating traces of people who were buffeted and bullied by the processes of history, whose identities and stories were struck from the records or who simply disappeared.

He collects particles of an archive that is not one: faces, bodies and body parts, the accounts of indigenous people, putative criminals, strangulation victims, mummies, inmates of a psychiatric hospital. In the Airmail Paintings, they become part of a post-colonial—or rather, de-colonial and nonlinear—chronicle that is riddled with rifts and gaps. Far from closing these rifts, Dittborn multiplies and enlarges them. Popular caricatures and their humorous abstractions of unfortunate circumstances dismantle the historic contexts and even shift some instances of real tragedy onto the plane of universal buffoonery. Moreover, copies from drawing instruction textbooks cycle through the pictures like a refrain in which a bed, a house, a car look like global archetypes for the localization of a subject in space and time. Only they are empty; the occupants are absent.

The Airmail Paintings envision individual and collective memory as a place that teems with the asynchronous rhythms of concealment and testimony, repression and conjecture, assertion and contradiction, death and coy smiles. These are also the rhythms of Dittborn’s art, which mischievously prevents history from being finalized because it distrusts last words as much as all other fixed states of affairs, including its own. And so these pictures travel onward, perpetuating the fractures, the losses, even the nescience and making them circulate in the world of exhibitions. Conveyed by messengers who knock on the door when an exhibition closes—ours will be no exception—to take away the stories that belong to everyone and no one.

Text: Alexander Koch

Translation: Gerrit Jackson

Photos: Ladislav Zajac, Alexander Koch, KOW

Review:

FLASH ART (Nov 20, 2014, by Patrick Armstrong)