If works of art carried as little social and political significance as some skeptics claim, would they be as hotly contested as they are, again and again? We can draw a mental timeline of iconoclasm from the statues and temples ISIS is currently smashing to pieces in Syria back to countless military campaigns, revolts, and regime changes in which the conquest of people went hand in hand with the plunder and destruction of their artistic treasures. Two exhibitions by Clemens von Wedemeyer and Dierk Schmidt highlight the political contentiousness of sculpture. The appropriation and exhibition of aesthetic objects is an inherent part of the struggle over dividing up the world. Schmidt examines the history of German colonialism, with a particular view to the politics of restitution and Berlin’s Humboldt Forum. But first, Clemens von Wedemeyer explores the cinema as a social scene and battleground that unfolds upon—but also behind, in front of, and around—the silver screen; a project he has pursued since 2002 in an oeuvre that has increasingly expanded into the genres of documentary environment, architectural installation, and sculpture.

Wedemeyer’s show is the eighth and final chapter in our yearlong program titled ONE YEAR OF FILMMAKERS. In the twentieth century, the moving image has dominated our field of vision and helped reshape how we see others and ourselves. The five-channel film installation THE BEGINNING. LIVING FIGURES DYING(2013) draws on the arsenal of scenes of conjuration and destruction in which the cinema has taken possession of the material images of man (and his gods and demons) by putting them on the screen. In a collage of historic footage, Wedemeyer traces how film staged the aura of bodily presence, animating objects and investing the human likeness with outsize magical power while also shattering it. A brief cultural history of sculpture in the movies in which Greek and Roman antiquity is the foil upon which the creation of a human figure as well as its demonization are projected, the video installation is also a historical catalogue of the implements of suggestion, the props, mockups, and effects, in which the cinema fabricated phantasms of the alien and menacing Other.

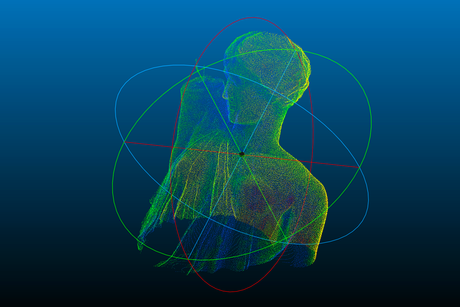

Wedemeyer’s exhibition builds on and extends the ensemble he produced for MAXXI in Rome. For the video installation AFTERIMAGE (2013), he created a detailed digital record of the interiors at CineArs, where props for Cinecittà, the hub of Italian filmmaking, have been manufactured since 1932—Cinecittà Holding is currently threatening to close the studio. Two statues that he scanned now resurface in the gallery’s basement showroom as 3D sand prints (2015). Resurrected by algorithms, the two sculptures embody a scene from Greek myth: after Zeus sent a deluge to destroy humankind for its depravity, Deucalion and Pyrrha were the only human beings left on the deserted earth. They consulted the oracle of Themis, who instructed them to cast the bones of their mother behind them. Initially baffled, Deucalion and Pyrrha eventually understood that they were children of the earth—so their mother’s bones must be the rocks at their feet. They threw them over their shoulders, and a young generation sprang up from the stones. A new humanity, born from dead matter. The sound installation is a joint work with the artists Moritz Fehr and Lukas Hoffmann.

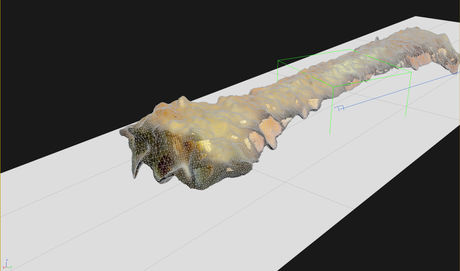

To make his sculptures, Wedemeyer harnesses techniques archaeologists use to reconstruct ancient temples and works of plastic art—and, in the future, to literally reprint objects destroyed in ravages like the one unleashed by ISIS in Palmyra. Iconoclasm is producing a new type of future artifacts from the past, artifacts that are clearly not what they once were and form a distinctive category of aesthetic objects. Another such object is A RECOVERED BONE (2014). In an act of digital theft, Wedemeyer lifted one of movie history’s most famous props from the screen and set it on a pedestal in the gallery. A key scene from Stanley Kubrick’s "2001: A Space Odyssey" tells the story of humankind’s earliest technological moment: a humanoid uses a bone as the first tool—and the first weapon—and then flings it toward the heavens in a gesture of triumph. Wedemeyer excised the object from the famous scene and reconstructed its shape using 3D modeling technology. The heavens are deserted, the bone is tangible, but each is as inauthentic as the other. Or is it?

3D and nanotechnology, AI, and other twenty-first-century developments herald the advent of novel metamorphoses that throw a different light on the animistic worldviews that speak from ancient stories. Images and spaces, information and bodies become mutually convertible; the boundary between animate and inanimate substance looks increasingly implausible, as do the distinctions between real people and their media incarnations, between genuine objects and mere dummies. Linear time is riddled with holes and folded in wrinkles. Artistic methods of reenactment, the theatrical recreation of past events, widen to include processes of material and immaterial transformation whose coordinates in time and space seem ever more mutable and inject historic moments of emancipation and critique into the social struggles of the present. Instants of resistance leap across the time of history.

In the final section of Wedemeyer’s exhibition, the mute bit-players and extras of a distant past rise up in a noisy rebellion against the movie industry, the “most powerful weapon in modern societies” (as Mussolini put it when he founded the fascist studio Cinecittà). Shot in Rome in 2013, PROCESSION: THE CAST, a film about the extras’ riots that rocked the Roman studio in 1958, features members of the Teatro Valle Occupato, a self-organized ensemble that came together in 2011 to prevent the closure of the historic Teatro Valle by taking the venue’s management into its own hands. Today’s cultural activists speak in the voices of yesterday’s insurgents. In 1958, the American film Ben Hur was shot at Cinecittà—also known as the Italian Hollywood—and thousands of unemployed locals sought work on the movie’s now-famous crowd scenes. When they were turned away, they stormed the studios: the political dimension of iconoclasm extends beyond the toppling of works of visual art to the social protest against the conditions under which they are produced.

Text: Alexander Koch

Translation: Gerrit Jackson

Editing: Kimberly Bradley

Photos: Ladislav Zajac, KOW

Reviews:

BERLIN ART LINK (Interview by Alice Bardos, Dec 18, 2015)

ZITTY (Jana J. Bach, Jan 25, 2016)

MOUSSE MAGAZINE (Interview by Isabella Zamboni, Feb 18, 2016)

SPIKE MAGAZINE (Interview by Marie-France Raphael, Feb 19, 2016)

FRIEZE BLOG (by Elisa R. Linn and Lennart Wolff, Feb 21, 2016)

SLEEK MAGAZINE (by Marie-France Raphael, Mar 3, 2016)

Wären Kunstwerke politisch so unbedeutend, wie manche Skeptiker unken, würden sie dann immer wieder so umkämpft? Von den Statuen und Tempeln, die der IS in Syrien zerstört, läuft ein ikonoklastischer Zeitpfeil rückwärts durch zig Feldzüge, Revolten und Regimewechsel, die neben Menschen auch deren Bildwerke eroberten und raubten oder zerstörten. Die Aneignung ästhetischer Objekte gehört zum Kampf um die Aufteilung der Welt. Clemens von Wedemeyer und Dierk Schmidt machen in zwei aufeinanderfolgenden Ausstellungen die Skulptur zum Politikum. Dierk Schmidt schaut auf die deutsche Kolonialgeschichte, mit besonderem Blick auf die Restitutionspolitik und das Berliner Humboldt Forum. Den Auftakt aber macht Clemens von Wedemeyer, der seit 2002 das Kino als einen sozialen Schau- und Kampfplatz beschreibt, der nicht nur auf der Projektionsleinwand liegt, sondern auch dahinter, davor und daneben. Immer öfter entstehen dabei dokumentarische Rauminszenierungen, architektonische Installationen und Skulpturen.

Mit Wedemeyers Ausstellung präsentieren wir das achte und letzte Kapitel unseres Jahresprogramms

ONE YEAR OF FILMMAKERS. Im 20. Jahrhundert hat das Bewegtbild die Vorherrschaft über das menschliche Antlitz erworben und ein ordentliches Wort darüber mitgesprochen, wofür wir uns und andere halten. Die fünfteilige Filminstallation

THE BEGINNING. LIVING FIGURES DYING (2013) greift ins Arsenal der Beschwörungs- und Zerstörungsszenen, in denen sich das Kino die materiellen Bilder des Menschen (und seiner Götter und Dämonen) zu Eigen machte, indem es sie auf die Leinwand brachte. Mit einer Collage historischer Aufnahmen rekapituliert Wedemeyers Installation, wie der Film die Aura des Plastischen inszenierte, wie er Objekte beseelte, das menschliche Konterfei magisch überhöhte und ebenso zerschlug. Es ist eine kleine Kulturgeschichte der Skulptur im Film, in der die griechische und die römische Antike als Projektionsfläche sowohl für die Erschaffung als auch für die Dämonisierung einer humanen Gestalt dienen. Zugleich ist es eine Chronik der suggestiven Werkzeuge, der Requisiten, Attrappen und Effekte, mit denen das Kino Phantasmen des Fremden, Anderen und Bedrohlichen erschuf.

Wedemeyers Ausstellung baut auf seiner Produktion für das MAXXI in Rom auf und führt sie weiter. Für seine Videoinstallation

AFTERIMAGE (2013) scannte Wedemeyer die Innenräume des Ateliers CineArs, das seit 1932 Requisiten für die italienischen Filmproduktionen der Cinecittà fertigt – der Fortbestand des Ateliers ist durch die Cinecittà Holding bedroht. Zwei Statuen, die dort digital erfasst wurden, finden sich nun im Untergeschoss der Galerie als 3D-Sand-Drucke wieder (2015). Neuerstanden aus Algorithmen sprechen die beiden Bildwerke mit künstlichen Stimmen eine Szene der griechischen Mythologie: Nachdem Zeus die verdorbene Menschheit mit einer Sintflut vernichtet hatte waren Deukalion und Pyrrha allein auf Erden. Einsam riefen sie das Orakel der Themis um Hilfe an, das sie aufforderte, die Gebeine ihrer Mutter über die Schultern zu werfen. Zunächst verdutzt erkannten sich Deukalion und Pyrrha schließlich als Kinder der Erde – die Knochen ihrer Mutter mussten also die Steine zu ihren Füßen sein. Sie warfen sie hinter sich und aus ihnen erwuchs eine kommende Generation. Die neue Menschheit, geboren aus toter Materie. Die Ton-Installation ist eine Gemeinschaftsarbeit mit Moritz Fehr und Lukas Hoffmann.

Wedemeyers Skulpturen nutzen Verfahren, die Archäologen bei der Rekonstruktion von antiken Tempeln und Skulpturen verwenden. Zukünftig auch, um sie nach einer eventuellen Zerstörung, wie etwa durch den IS im Falle Palmyras, buchstäblich neu ausdrucken zu können. Der Ikonoklasmus bringt eine neue Sorte künftiger Artefakte aus der Vergangenheit hervor, die freilich nicht sind, was sie einmal waren und eine eigene Kategorie ästhetischer Gegenstände bilden. Ein solcher Gegenstand ist auch

A RECOVERED BONE (2015). In einem digitalen Diebstahl hat Wedemeyer eine der berühmtesten Requisiten der Filmgeschichte von der Leinwand entwendet und im Ausstellungsraum auf einen Sockel gesetzt. Eine Schlüsselszene in Stanley Kubricks "2001. Odyssee im Weltraum" beschreibt den ersten technologischen Moment des Menschen: Ein Humanoider verwendet einen Knochen als erstes Werkzeug und zugleich als erste Waffe. Triumphierend schleudert er ihn gen Himmel. Wedemeyer hat ihn aus der berühmten Szene herausoperiert und mit 3D-Verfahren plastisch rekonstruiert. Der Himmel ist leer, der Knochen greifbar, authentisch sind beide nicht. Oder?

Mit 3D-, Nano-, KI- und anderen Technologien treten im 21. Jahrhundert neue Metamorphosen auf den Plan, die animistische Weltbilder aus den antiken Erzählungen in neuem Licht erscheinen lassen. Bilder und Räume, Informationen und Körper werden ineinander konvertierbar, die Grenze zwischen belebter und unbelebter Substanz verliert ebenso an Plausibilität wie die Unterscheidung zwischen realen Personen und ihren medialen Inkarnationen, zwischen echten Dingen und bloßen Attrappen. Die lineare Zeit hat Löcher und Falten. Künstlerische Methoden des Re-Enactments, der Wiederaufführung vergangener Ereignisse, öffnen sich auf materielle und immaterielle Transformationsprozesse in immer beweglicher scheinenden Zeit- und Raum-Koordinaten. Sie schließen dabei auch historische Momente von Emanzipation und Kritik mit sozialen Auseinandersetzungen der Gegenwart kurz. Augenblicke des Widerstands springen über die historische Zeit hinweg.

Im letzten Teil von Wedemeyers Ausstellung erheben sich die stillen Komparsen und Statisten einer untergegangenen Epoche zum lauten Aufstand gegen die Filmindustrie, der „stärksten Waffe in modernen Gesellschaften“ (so Mussolini über die Gründung des faschistischen Filmstudios Cinecittà). In den Rollen des 2013 in Rom gedrehten Films

PROCESSION: THE CAST über die römischen Komparsenproteste von 1958 sehen wir Mitglieder des Teatro Valle Occupato, die sich 2011 organisierten, um der Schließung des historischen Teatro Valle mit einer eigenen, selbstverwalteten Organisation zu begegnen. Die Kulturaktivisten von heute übernehmen die Stimmen der Aufständischen von gestern. Als 1958 die amerikanische Produktion "Ben Hur" im italienischen Hollywood Cinecittà gedreht wurde, hofften Tausende Arbeitslose auf einen Job bei den berühmt gewordenen Massenszenen. Als sie zurückgewiesen wurden, stürmten sie die Filmstudios: Die politische Dimension des Ikonoklasmus liegt nicht nur im Sturz der Bildwerke, sondern auch im sozialen Protest gegen ihre Produktionsbedingungen.

Text: Alexander Koch

Photos: Ladislav Zajac, KOW

Reviews:

BERLIN ART LINK (Interview by Alice Bardos, Dec 18, 2015)

ZITTY (Jana J. Bach, Jan 25, 2016)

MOUSSE MAGAZINE (Interview by Isabella Zamboni, Feb 18, 2016)

SPIKE MAGAZINE (Interview by Marie-France Raphael, Feb 19, 2016)

FRIEZE BLOG (by Elisa R. Linn and Lennart Wolff, Feb 21, 2016)

SLEEK MAGAZINE (by Marie-France Raphael, Mar 3, 2016)