Feb 18 – April 9, 2017

More light! Build more lighthouses! Drink phosphorus! As autocrats and neo-feudalists in the United States, Turkey, Poland, Great Britain, and other countries turn off the lights, something must shine the brighter. But what? What should be done? Chto Delat?! That is the signature question under which this collective of artists, intellectuals, and activists from Moscow and Saint Petersburg have worked together for the past fourteen years. In 2014, however, the group ran out of answers—in an EXHIBITION AT KOW, they sealed their hopes that art might offer a critical response to the war in Ukraine and Putin’s neo-nationalism in a time capsule and launched them toward an unknown future. The show was an open admission of their perplexity and marginality. The shock that had agonized the Russian collective has now reached the West. They have worked through it and are coming back to Berlin with a fresh look at their prospects and ours—and, at KOW, they build a lighthouse.

Nothing less is at stake than the fate of the Enlightenment, an increasingly global state of emergency, and the ruined illusion that liberalism might survive on a few islands. Also at stake is a possible way for art to keep speaking up. The upstairs gallery memorializes men and women who were burned or shot to death or killed by water guns in recent protests. Towering above the five sculptures commemorating the brutal demise of free public expression is a lighthouse scaffold that takes inspiration from Gustav Klutsis’s agitprop kiosks, a historic form of mass communication that effectively publicized progressive ideals after the Russian Revolution. But instead of broadcasting confident messages rallying the masses to build a better future, Chto Delat raise a monument of gloom, a black beacon of mournful uproar, as well as a transmitter mast for the saturnine incantations of recently deceased writers and musicians, from John Berger to Leonard Cohen, who knew about the power of darkness and now chant a requiem for the fallen heroes of freedom.

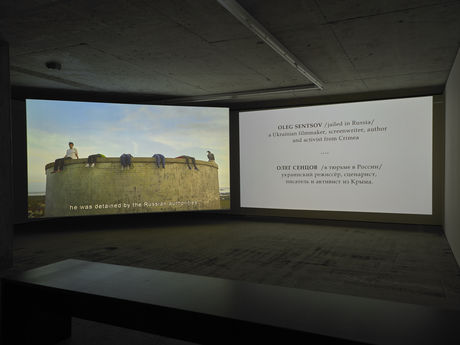

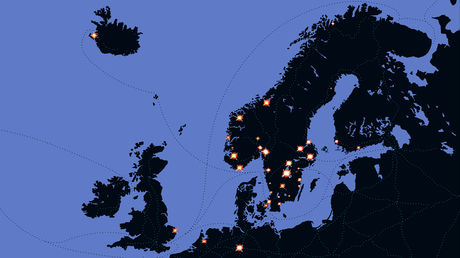

Lighthouses may illuminate the world around them, but the signal they send is a warning. They mark places that navigators had best avoid. In the downstairs gallery, the lighthouse becomes the symbol of a refuge that has lost its way. In cooperation with ARTISTS AT RISK, a nonprofit that organizes stays in so-called “Safe Havens” in Europe for artists who are under threat, Chto Delat shot the film “It Has Not Happened to Us Yet. Safe Haven”(1) on the Norwegian island of Sula in 2016. Their two-channel video installation tells the fictional story of five artists whom a fellowship enables to escape war and repression for a remote islet. Interspersed in the narrative are documentary shots: in interviews, the islanders explain their solidarity with refugee artists, gladly explain local rules and the conditions for social integration, and sing the island’s hymn. But it gradually emerges that the artists’ hope to leave the world’s conflicts and their own disputes behind for a peaceful exile was an illusion. The story might well become Chto Delat’s own future, or that of many others, and it reminds us of the countless individuals who had or still have nowhere to escape to.

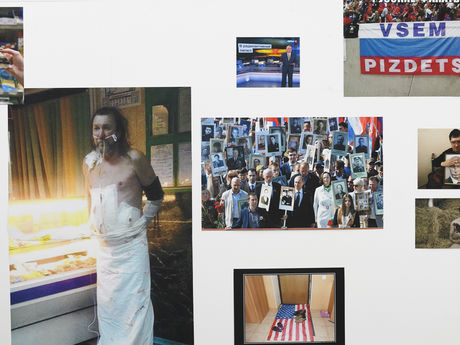

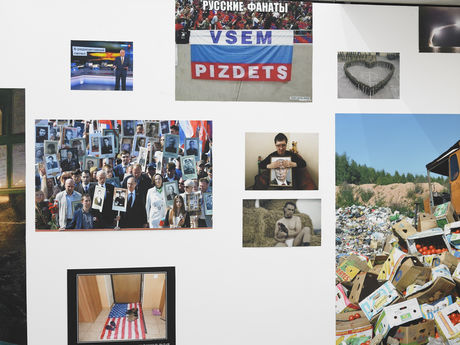

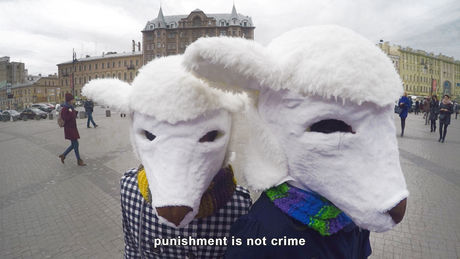

A few steps away is Putin’s reality. In an expansive assemblage of images found on the Internet, Chto Delat document how the new Russia perpetually produces politics and everyday life as performative rituals that proliferate in social media. We stand amid the theater of sometimes utterly absurd gestures and emblems of neo-national identity to observe an experiment: a monitor shows a public square in Saint Petersburg. One after another, three demonstrators appear wearing signs around their necks that read: “Hug me, I’m your enemy,” “Beat me, I’m your sister,” “Pinch me, I’m dreaming you.” Passersby and actors respond in different ways to the quiet protesters’ appeals, revealing, en passant, the surreal nature of public life beneath the banner of the Russian Bear. Who is telling the truth? Who is playing a part? Who speaks for whom? Who is being threatened, and by whom?

Chto Delat’s exhibition is a statement on the political present moment. It responds to the ever more aggressive attacks on liberal values and revisits historic—and yet not entirely historic—episodes of anxiety, flight, and powerlessness. Here are Walter Benjamin, Trotsky, and Hannah Arendt, intellectuals forced into exile; here are Bertolt Brecht’s observations on the disintegration of the German public sphere in the run-up to the Nazis’ rise to power. Each might be matched to a similar figure today, their situation now made worse by a new global condition: the ideas of equality and justice have fewer and fewer passionate defenders—they seem to have become dispensable in the “prolonged twilight of reaction,”(2) as Chto Delat put it in their notes accompanying the exhibition. If some optimistic light nonetheless glimmers in our galleries, it is due to the confidence of a collective of unflinching thinkers and practitioners who, when asked what should be done, would throw in that art at least sees possibility even when the lights go out.

Call it their keen sense of reality. Or in Leonard Cohen’s words, “There’s a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in.” Chto Delat’s exhibition was fabricated in the galleries at KOW and in Petersburg in the weeks before the opening. In 2017–2018, it will travel to various locations and keep growing. New productions are scheduled in which theatrical and documentary forms will be interwoven. The social and institutional staging of reality calls for commensurate choreographies of critique, complemented by poetry, sculpture, and an enlarged repertoire of capacious installation art that translates progressive forms from Russian avant-garde and Soviet culture across boundaries of genre and ideology into a queer popular aesthetic. In the face of a world (and an art world) that is variously dumbstruck, ensconced in elitism, or dissipated in foolish chatter, Chto Delat are committed to a language that stands by its ideals, that seeks to make itself understood, and continue to regard social emancipation as the unchanging mission of their shared work.

(1) “It Has Not Happened to Us Yet. Safe Haven” was curated by Perpetuum Mobile, co-produced by LKV and Chto Detalt, funded by URO/KORO

(2) Dmitry Vilensky, Chto Delat, January 2017

Text: Alexander Koch

Translation: Gerrit Jackson

In January 2017, Dmitry Vilensky of Chto Delat writes about the exhibition at KOW:

One of the Chto Delat Collective's 2014 exhibitions was entitled Time Capsule: Artistic Report on Catastrophes and Utopia. In it, we were searching for a visual language capable of reflecting our state of shock and perplexity in a moment when the very foundations of our work, together with social and personal relations and our belief in the possibilities of politics and art, began to collapse before our eyes. This situation, which may be described as extreme, critical, exceptional, gradually became the norm of our everyday existence. And our activities were forced to somehow reflect that situation – the rapid narrowing of the public sphere, constantly increasing marginalization of the ideas we value, departure of close friends, post-truth (losing any way of distinguishing fact from fiction), the disappearance of a group of friendly institutions and core funding for our work. If earlier, the concept of the state of emergency as a norm in political history had always been present in our analysis, now that situation itself began to actually control our entire lives, wielding its own absurd sovereignty.

Now, having since adapted to this new condition, we have begun increasingly to perceive the situation rather through the despairing lens of Ukrainian artist Nikita Kadan: “…. what was on the extreme right has crept into the enlightened centre …. Аnd, what was on the extreme left crumbled into the outer darkness, where there is weeping and gnashing of teeth. The Left, the diehard post-Soviet Left, famished materialists, anemic educators, fine-boned humanists. How is it beyond the fringe? How is the darkness? Can you make out each other’s figures? Is it too late to be afraid?» (1)

If earlier this sounded like a diagnosis of the Russo-Ukrainian situation, in which we felt our exceptional / excluded position, we now see how this condition has crept and spread throughout the world, when you can no longer understand what country the Facebook post you are reading is from—it might be from England, Hungary, Poland, Egypt, Israel, Turkey, or the United States?

***

The situation in Russia remains unique in terms of the low level of resistance – here we can directly quote Brecht’s gloomy remark in his poem “To Posterity,” where he writes of “…when there was only injustice and no resistance.” But even here the question is not yet settled, many scenarios have not yet played out, and we still have the chance to speak, to find like-minded people and to struggle together, as it has been throughout all these years, full of exciting creative work, obsession, inspirations, and hopes. The darkness, about which, following Christian tradition, there has always been so much talk on the Left, has not yet closed in. What we are living through is rather a prolonged twilight of reaction. A period of global transformation.

Some speak of the collapse of the humanist project, others of the menace of the dark Enlightenment, a return to a new Middle Ages. Many have no firm grasp of anything other than a general feeling of disorientation, depression and powerlessness. But it is important to acknowledge this condition, not as the latest outburst of a moribund conservatism familiar to us from history, but as the scenario of a different kind of universal global condition, in which the ideas and values on whose behalf we long ago decided to fight are not provided for– they simply are not needed. The radical new ideas of progress and contemporaneity have been put forward which no longer require equality and justice – the Enlightenment tradition has once again been revealed to be fragile and abandoned, in need of new reinterpretation and defense.

***

Perhaps this threat will force us to reconsider many things and to band together with renewed vigor?

After all, we have nowhere to flee– there is no place left where the old Enlightenment consensus has not, to some degree or other, been placed in jeopardy. And the challenge of encroaching darkness must be taken up.

This can be done mystically, as Agamben proposes: "Is darkness not an anonymous experience that is by definition impenetrable; something that is not directed at us and thus cannot concern us? On the contrary, the contemporary is the person who perceives the darkness of his time as something that concerns him, as something that never ceases to engage him. Darkness is something that— more than any light—turns directly and singularly toward him. The contemporary is the one whose eyes are struck by the beam of darkness that comes from his own time."

Or we can turn to Hannah Arendt and her re-reading of the tale of Danko*: "Even in the darkest of times we have the right to expect some illumination, and that such illumination may come less from theories and concepts than from the uncertain, flickering, and often weak light that some men and women, in their lives and works, will kindle under almost all circumstances and shed over the time-span that was given them on earth." (3)

Or, as Leonard Сohen sang: “there is a crack in everything that's how the light gets in.”

Light—you never know where it comes from.

To become more porous. To produce more holes, cracks, and lighthouses. To drink some phosphorus.

Notes:

The text reflects recent discussions and publications and I would like to express my gratitude to certain authors who participated in those– namely, Mikhail Kurtov for his text “Рассеянность, растерянность, пористость: три режима эстетического” (Absentmindedness, Confusion, and Porousness: Three Regimes of the Aesthetic), the collective of the journal Просторы (Expanses) for a discussion of darkness, and Taus Makhacheva for her poetic observations.

1) From Nikita Kadan’s text “Зерна” (Sees), published on the internet in the journal Просторы http://prostory.net.ua/ua/avtorski-rozdily/sections/32-zerna/64-zerna

2) From Giorgio Agamben’s article “What is the Contemporary?” from What is an Apparatus? and Other Essays, trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella (Stanford University Press, 2009), p. 45.

3) From Hannah Arendt’s book Men in Dark Times, p. xi.

* A tale written by Maxim Gorky about a hero who in order to light his people’s way out of slavery tore out his heart, which shined like a flame.