Artistic Report on Catastrophes and Utopia

Feb 28–Apr 18, 2015

Following Chto Delat's solo exhibition at SECESSION VIENNA this winter, we present the first gallery solo project of the Russian collective. It is the third chapter of our exhibition series ONE YEAR OF FILMMAKERS.

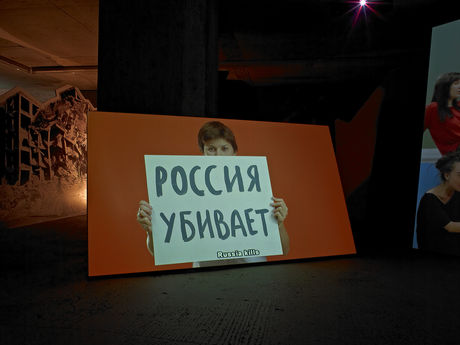

The events of recent months have confronted the Russian artist collective Chto Delat with a changed reality: “A new Cold War atmosphere, an escalating search for enemies, ever-tighter repression of all dissent, and an open military confrontation with Ukraine leaving thousands of dead on both sides.”(1) Now the Saint Petersburg-based Chto Delat (the name means “What Is to Be Done?”) explore “what art could be at a moment when familiar politics and everyday life start falling apart (…) audiences vanish, activist groups implode and actually getting anything done becomes impossible.” They conclude: “We lost. We are excluded from this society, in which 80 percent of the population supports the war.” In their first exhibition at KOW – a modified version of their earlier project at the Secession in Vienna – Chto Delat report from a cataclysmic present that struck their ability to imagine an alternative, a future. With a view to the current situation in Russia and beyond, they paint a picture of widespread resignation in the face of today’s economic as well as military imperialism, resurgent nationalisms, and the return to confrontational postures on both sides of the former East-West conflict.

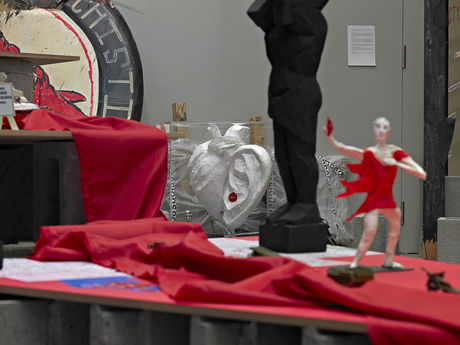

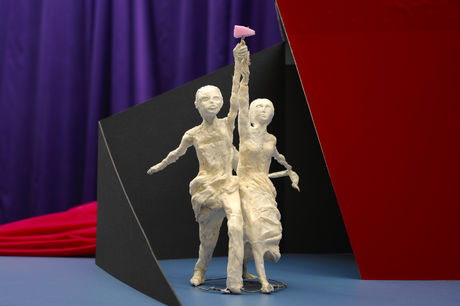

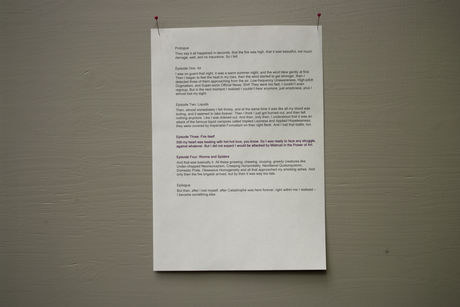

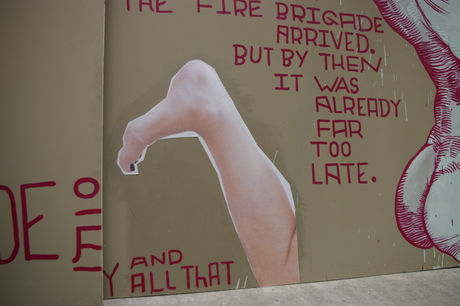

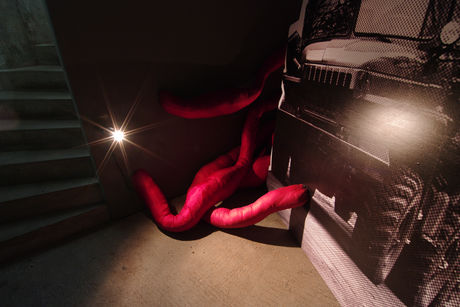

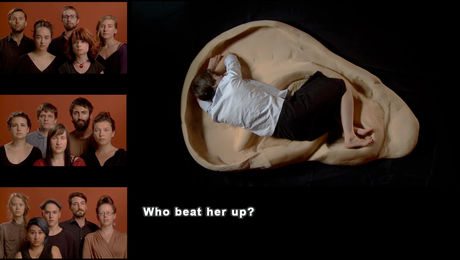

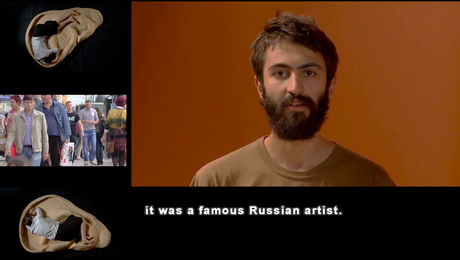

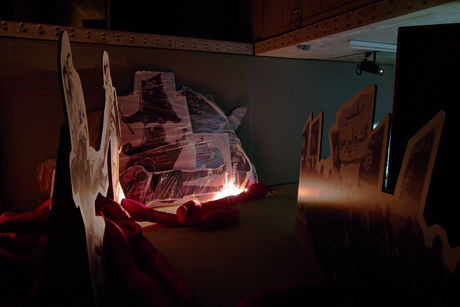

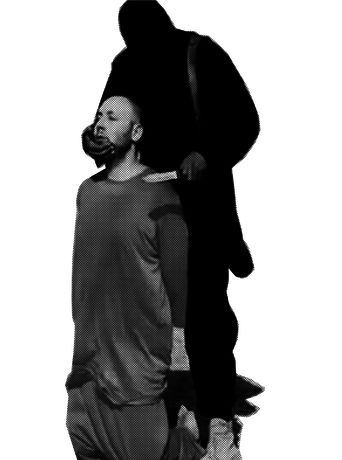

Someone is burning. Burning up from the inside. First his senses fail, then his heart catches fire, and finally the flames consume hope itself. It is the key scene of the exhibition: a text on the mutilation of a self – his body, his perception, his ideals – penned by Chto Delat as the inner voice of their anti-fascist sculpture "Our Paper Soldier", which was DESTROYED BY ARSON ON JUNE 24, 2014. The 20-foot monument was created for the Vienna Festival and then traveled to Berlin for the Berliner Festspiele. One night, unknown perpetrators doused it with gasoline and put a match to it. “I did not expect I would be attacked by mistrust in the power of art,” the artists have their charred soldier say, and then, “after I lost myself, after catastrophe was there forever, right within me, I realized – I became something else.” What was he becoming? The gutted work returned as an undead combatant. Resurrected in the fall as a queer zombie monument for the Vienna Secession, it has now come back to Berlin for our exhibition. Headless, its chest torn open, one wing dangling lifelessly, it looms in the gallery space like a battered angel of history. A shattered Phoenix, it rises amid toylike sceneries, including a miniature stage set of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, as well as visual fragments from past film productions and scraps of personal recollections compiled by Chto Delat; the artists have added several new pieces to the arrangement.

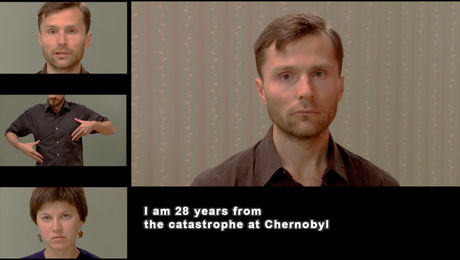

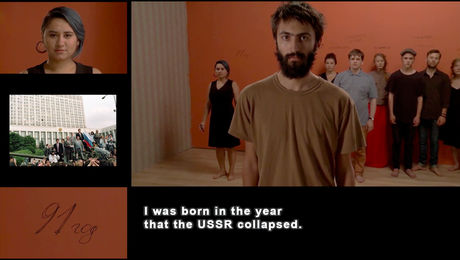

It is almost as though the Russian collective’s artists, intellectuals, and activists sought to reassure themselves of the distinctive language they have developed over the years in numerous films, performances, images and objects, events and publications – to reassert their aspiration to a forward-looking thinking that can imagine a future different from the one that is charted for us and supposedly without alternative. Then again, this language seems to surrender, its aspiration to articulate a public voice in a time of war blasted. In KOW’s downstairs gallery, the calamity unfolds in its full global reach. Blown-up newspaper imagery turns it into a labyrinth – Syria, Ebola, and ISIS, military convoys and rutting Russian oligarch bears. At the center sits a four-part video installation called "The Excluded, in a Moment of Danger". Activist friends and graduates of the School of Engaged Art that Chto Delat operate in Saint Petersburg take stock of where they stand: orphaned agents of history, they recount their own history. They discuss the events until, in mid-speech, their voice loses all meaning; they crack up, stand up, become bodies, and come together: a community of people who are awake and perplexed, afraid and alert, who need each other.

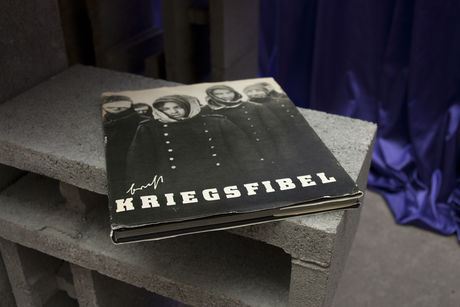

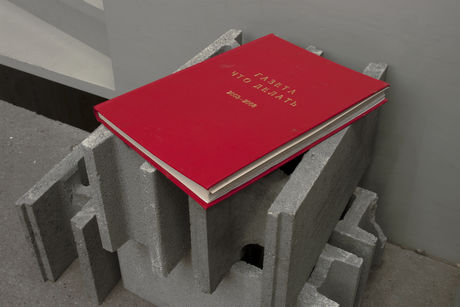

Founded in Saint Petersburg in 2003, Chto Delat has sought to revive the tradition of the Russian avant-gardes and their contribution to the revolutionary optimism of the period. The group has taken a stand against Vladimir Putin’s regime and championed a communist alternative to capitalism. Its repertoire has included Brechtian songspiels, participatory theater, learning murals, public actions, and propaganda designed to counter the authorities’ management of public opinion; in a newspaper, of which 38 issues have appeared to date, they have interwoven their artistic praxis with philosophical and political discourses. Chto Delat has steadfastly held on to the utopian idea that another life is possible and used art to limn its outlines. Yet after numerous exhibitions in multiple countries, their show at KOW marks a turning point. Some Operaists and Accelerationists believe that all we need to do is give capitalism a little push toward the cataclysm that is its inevitable fate. In her MANIFESTO FOR ZOMBIE-COMMUNISM, the Chto Delat member Oxana Timofeeva counters: We are already surrounded by a full-blown cataclysm, and it will never resolve itself. To keep on living as we have, she argues, is not a viable choice – yet for the time being the question “What Is to Be Done?” is left without an answer.

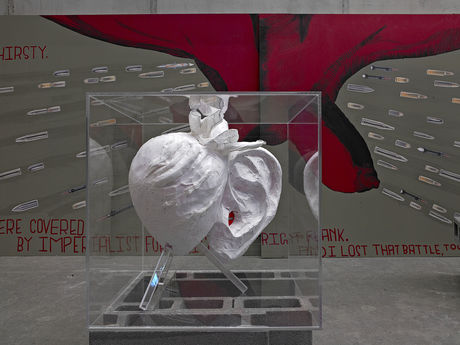

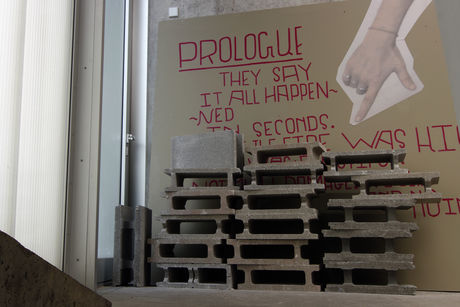

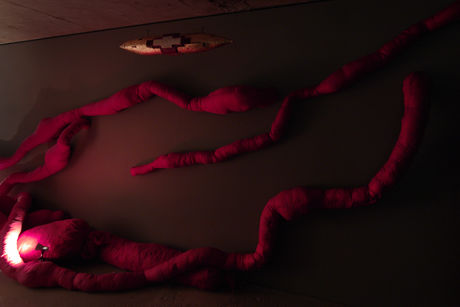

“Until there is no hope, true revolutionary action is postponed,”(2) Timofeeva writes, rejecting both the wait-and-see and the accelerationist variants of optimism. “Forget hope: revolution starts in hell.” And hell is the now, a place where we can neither live nor die and burn in eternity amid the consequences of past deeds. In a paradoxical twist, Chto Delat conclude that they wish to step outside the course of history itself. Under the eyes of a headless angel of history, they suspend their hope for change to make room for an inconceivable change, an unknowable revolution that may come one day or another and with which history will recommence. A display case in the gallery contains a paper heart fused to an ear; inwardness inextricably bound up with awareness of the outside world. It is a time capsule in which the collective’s members dispatch personal objects into a nameless future, deferring the possibility of a different life to another day. The ear is stopped up with a red plug inscribed with "Chto Delat?". A self-willed sensory deprivation to shield them against the noise of an insane contemporary world?

Can an exhibition convey this deeply skeptical view of hope – and of art? KOW’s curatorial approach in adapting "Time Capsule. Artistic Report on Catastrophes and Utopia", Chto Delat’s first monographic show at a gallery, is guided by the impulse to balance the production on a threshold of uncertainty. The gallery space becomes a theater cluttered with props. Elements from the exhibition at the Secession such as a 125-foot-long wall painting created in response to Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze appear in fragmented form. No longer unambiguously works of art, half presented on the forestage, half stored backstage in a waiting loop between two performances, the objects on display find themselves in doubtful terrain; their function and status have become questionable. Representation is cracking.

On April 9, Dmitry Vilensky from Chto Delat will come to the gallery at 7pm to discuss the project with Alexander Koch from KOW.

Chto Delat members are Tsaplya Olga Egorova, Nina Gasteva, Nikolay Oleynikov, Gluklya Natalia Pershina, Alexey Penzin, David Riff, Alexander Skidan, Oxana Timofeeva, and Dmitry Vilensky. Over the years, numerous Russian and international artists and intellectuals have contributed to the collective’s work.

(1) Tsaplya Olga Egorova, Nikolay Oleynikov, and Dmitry Vilensky, preface, Time Capsule: Artistic Report on Catastrophes and Utopia, Chto Delat newspaper, no. 38, November 2014.

(2) Oxana Timofeeva, "Manifesto for Zombie-Communism", in: Mute Magazine, January 12, 2015.

Text: Alexander Koch

Translation: Gerrit Jackson

Editing: Kimberly Bradley

Photos: Ladislav Zajac, Alexander Koch

Reviews:

ARTSLANT (Jan 2015, by Teodora Kotseva)

032C MAGAZINE (Mar 3, 2015, Interview with Chto Delat)

MONOPOL (Mar 12, 2015, Interview with Chto Delat)

BERLIN ART LINK (Mar 11, 2015, by Alena Sokhan)

WELT AM SONNTAG (Mar 22, 2015, by Gesine Borcherdt)

E-FLUX CONVERSATIONS (Apr 2, 2015, by Ana Teixeira Pinto)

SEE VIDEO

READ NEWSPAPER BY CHTO DELAT

Statement by Chto Delat:

What could art be at a moment when familiar politics and everyday life start falling apart? The events of recent months have thrown Russian artists and creative workers into a completely new reality: a new Cold War atmosphere, an escalating search for enemies, ever-tighter repression of all dissent, and an open military confrontation with Ukraine leaving thousands of dead on both sides.

What seemed the stuff of nightmares yesterday is becoming reality today, and artists who want to address present conditions have wound up in a very complicated position. How can we carry on creating, speaking and living when we are all frozen at our computer screens in hopeless anxiety, trying to make sense of the bloody mixture of contradictory and manipulated information, seething hatreds, madness and desperation while the chance to be heard is ever more limited? Most things we liked to speculate about – relations between art and politics, activism and participation – simply stop functioning. Worse, they become irrelevant in a suffocating climate of nationalistic paranoia. And we face this desperate situation while audiences vanish, activist groups implode and actually getting anything done becomes impossible. And so on.

An important peculiarity of the events taking place today in Russia and Ukraine is that they are positioned primarily in relation to the past: the unresolved trauma of the clash between Nazism and Stalinism and the crude manipulation of these ideologies that's now going on. All this provokes the sensation that the demons of the past have returned to strangle us with their tentacles of blood. In this publication we collected several reports on the developing situation in Ukraine and Russia, providing necessary insights into the context of our work and linking it to the wider world picture.

We feel affected by the general atmosphere of fear. Russia is afraid of the West. The West is afraid of Russia. Everywhere, it seems, people live in the expectation of new catastrophes, prevented from trusting each other or building a better future by the miserable blackmail of a status quo disguised as the only escape from a bigger disaster. In many places the fear of civil war is getting closer. Do we still have any hope for the future or is that gone? Are we desperate enough that we finally have nothing to lose? Or not yet? Perhaps our best hope lies in life after death, because we are already non-existing in a true revolutionary sense? A life after the collapse of all illusions and desires, with nothing left to wait for and the future no longer playing any role. Should we put up with this or can we break the chain of past and present catastrophes?

For our Secession installation we took as a starting point the very short and tragic story of one art object created by our collective in Vienna for the "Into the City" festival: "Our Paper Soldier" sculpture, conceived as a Queer replica of the monument to the Soviet soldier killed fighting for the liberation of Vienna from Nazism in 1945. This sculpture became a central part of our festival, asking the questions: “What is monumental today?” and: "What might constitute anti-fascist struggle in our time?" After the festival ended, the sculpture went to Berlin, where it was set on fire by persons unknown. So today we have decided to play with this story. In the midst of our work at Secession, we decided to make a new sculpture piece: a sculpture of a resurrected (zombie) soldier who somehow returns to Vienna and remains surrounded by iconic images of catastrophes recently happening in the world. With this gesture we want to demonstrate that all repressed and destroyed memories have a chance of another life, and that this life – the zombie state of the world – has a serious potential to interfere and to change the course of the future if we open up to its traumatic experiences.

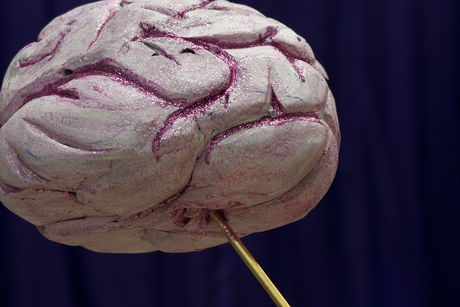

We also offer an alternative story in which our paper soldier becomes a zombie, a symbol of catastrophe or...an angel of history. In a mural frieze within the installation, the visual narrative invokes the dying dream of our fragile fallen hero at the moment when s/he burned in Berlin in July 2014. In the dream s/he sees him/herself attacked by such monstrous creatures as high-pitch dogmatism, loneliness, mass hysteria, hate-speech, imperialist formalism, crawling horizontality, separative individualism, and the kind of cynical conformism that Pasolini called qualunquismo). In each battle our fighter loses parts of his/her body one by one: sense organs, legs, arms, heart, guts. Only in losing him/herself completely does s/he take on another form of being, like a phoenix, a Phoenix of History that might finally win the main battle for Memory, the battle over Time.

This is why we put the Time Capsule in the middle of the show: to hook the future. Time capsules may hold messages filled with ideological pathos, as in the Soviet tradition, or they could contain leftovers of the everyday as in Andy Warhol's boxes, but they all share the same core idea – the belief that someone in the future will be able to encounter the contents. And this means we can connect ourselves to the future. Our time capsule has the shape of a heart connected to an ear. Each of us laid one special thing, something dear to him or her, in an empty space inside the heart. Then we sent this “heart-ear capsule” into the future. Because we believe the future will happen. Let’s make sense together out of this simple fact.

Tsaplya Olga Egorova, Nikolay Oleynikov and Dmitry Vilensky (with inspirations from Oxana Timopheva)