Chris Martin

Sep 11–Oct 24, 2010

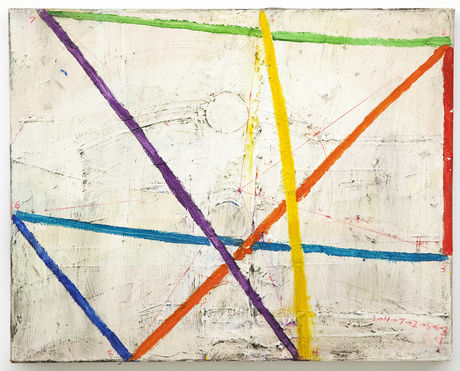

If Barnett Newman had listened more to James Brown records, perhaps his rigid “Zips” would have gotten a bit more swing–which would have given the elevated rhetoric of the color field painting certainly a bit more of a snap. But for a long time, African American sounds and abstract painting were not to be put together. The high arts were still strictly separated from the popular arts and also politically they were not a good fit: During the Cold War abstract art embodied the supremacy of Western Modernism versus Socialist Realism, while black pop music for instance accelerated the March to Washington in 1963, the highlight of the protests against the racial segregation in the USA.

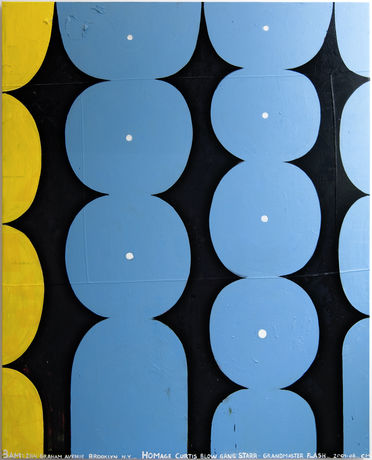

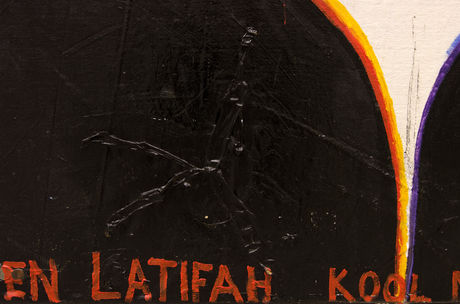

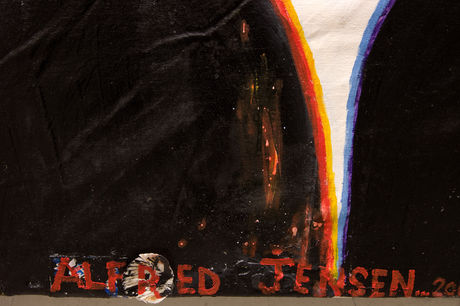

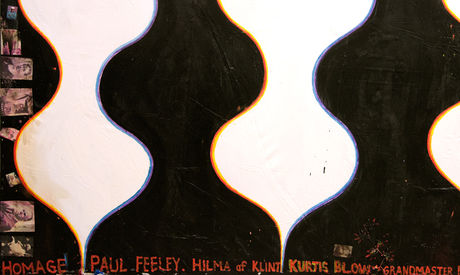

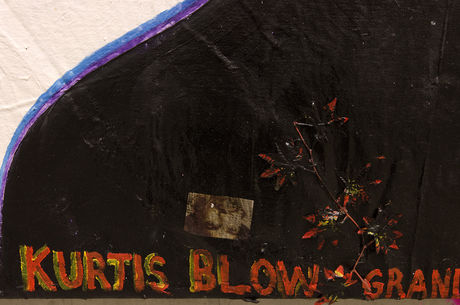

Chris Martin, born in 1954 in Washington D.C., was shaped by black music. “Dance” of 2008 can be formally considered as homage to Matisse, using the tools of color field painting. Then at the bottom of the 3,4 x 6,1m large canvas, there is a dedication to the grandchildren of James Brown, seventies pioneers and eighties icons of Hip Hop and Rap: Kurtis Blow, Grandmaster Flash, Kool Moe Dee and others. They made the spoken-song from the ghettos popular, invented DJ-ing and sampling–techniques of the postmodern culture. Further, the inscription involves the Swedish artist, spiritualist, and anthroposophist Hilma af Klint (1862−1944), Alfred Jensen (1903−1981), a classic representative of the New York School as well as his lesser known contemporaries Paul Feeley (1910−1966) and Myron Stout (1908−1987).

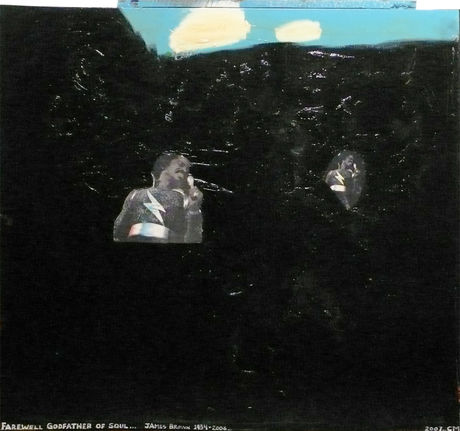

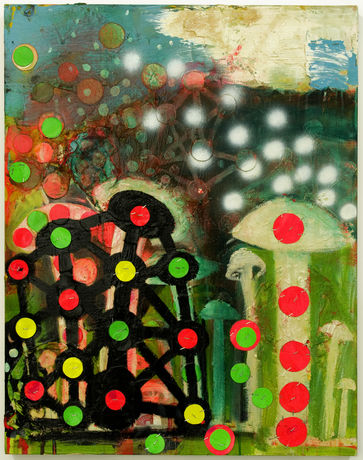

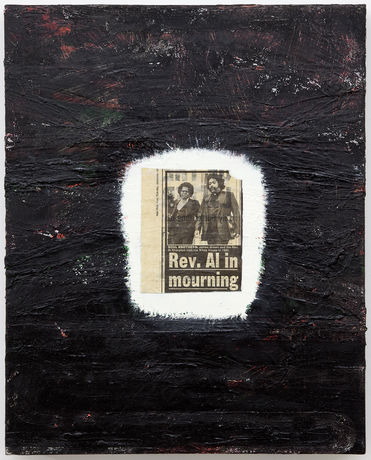

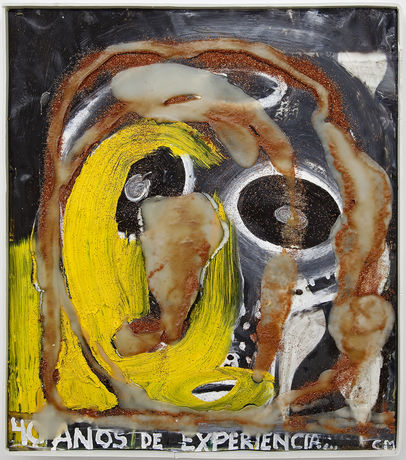

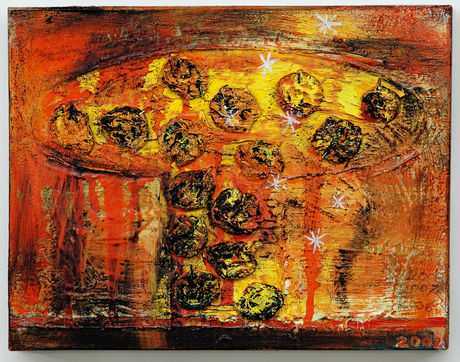

Since the mid nineties, Martin has often dedicated his canvases to artist colleagues he esteemed and honored as painters or as musicians–pop stars as well as those who were and are outside of the mainstream. Sometimes, as is the case withMichael Jackson, James Brown or Frank Moore, the inventor of the Red Ribbon for Aids solidarity, on the occasion of their deaths. Such dedications make Martin’s large-sized compositions rise from a societal foundation. They are gestures of devotion and solidarity. At the same time they disrespect any purity requirements of monochrome or color field painting. The names are rudely placed into the image’s space, right next to glued-in money coins, vinyls, banana peals, and newspaper articles.

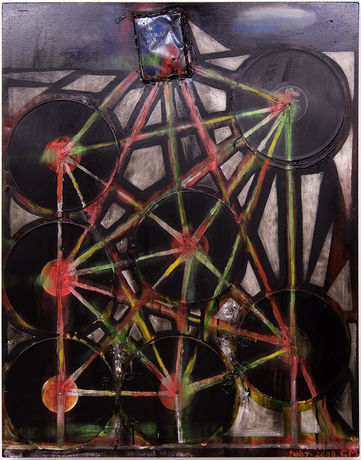

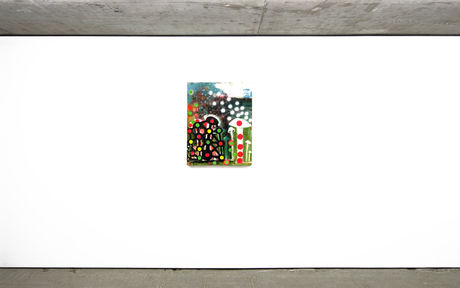

In spite of the rugged, through and through profane image surfaces, for more than 30 years Martin’s work has been connecting to different traditions of spiritual abstraction, for which New York, where Martin has been living since 1975, was the melting pot. Martin considers Indian folklore, Buddhist and Christian mystic or anthroposophist symbols, as well as the “Spiritual Landscapes” of the North American Romanticism, quite unknown in Europe. But especially in the sanctuary of modern abstraction, in the aesthetics of the sublime, Chris Martin poaches without reservation. He allows for the Pop Art heritage to rule in this domain where things often appear ethereal. Even here, especially here, he embraces the fusion of high and low as well as the trivialization of the image. Since for the human mind to meet its borders and to shiver in humility, does it need more than a hand full of psilocybin mushrooms, those which often glisten from Martin’s paintings and a pile of good records to tune in? Chris Martin contradicts the idea that the higher the art reaches, the thinner the air gets. Where things lift off the air gets thick.

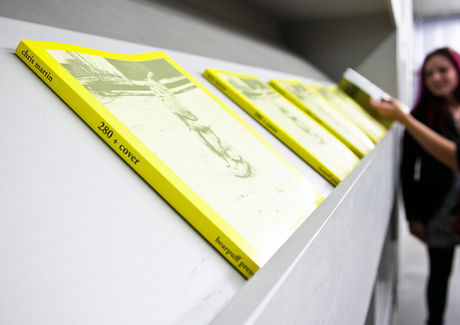

Chris Martin lives in Brooklyn, New York. He is a regular writer for The Brooklyn Rail, where he has published interviews with Brice Marden, Leon Golub, James Siena, Helmut Federle and others (www.brooklynrail.org). We show his first monographic exhibition outside the US.

Text and photos: Alexander Koch; image 2, 3, 25, 35 and 36: mickmorley

Translation: Staphanie Berger

Chris Martin, born in 1954 in Washington D.C., was shaped by black music. “Dance” of 2008 can be formally considered as homage to Matisse, using the tools of color field painting. Then at the bottom of the 3,4 x 6,1m large canvas, there is a dedication to the grandchildren of James Brown, seventies pioneers and eighties icons of Hip Hop and Rap: Kurtis Blow, Grandmaster Flash, Kool Moe Dee and others. They made the spoken-song from the ghettos popular, invented DJ-ing and sampling–techniques of the postmodern culture. Further, the inscription involves the Swedish artist, spiritualist, and anthroposophist Hilma af Klint (1862−1944), Alfred Jensen (1903−1981), a classic representative of the New York School as well as his lesser known contemporaries Paul Feeley (1910−1966) and Myron Stout (1908−1987).

Since the mid nineties, Martin has often dedicated his canvases to artist colleagues he esteemed and honored as painters or as musicians–pop stars as well as those who were and are outside of the mainstream. Sometimes, as is the case withMichael Jackson, James Brown or Frank Moore, the inventor of the Red Ribbon for Aids solidarity, on the occasion of their deaths. Such dedications make Martin’s large-sized compositions rise from a societal foundation. They are gestures of devotion and solidarity. At the same time they disrespect any purity requirements of monochrome or color field painting. The names are rudely placed into the image’s space, right next to glued-in money coins, vinyls, banana peals, and newspaper articles.

In spite of the rugged, through and through profane image surfaces, for more than 30 years Martin’s work has been connecting to different traditions of spiritual abstraction, for which New York, where Martin has been living since 1975, was the melting pot. Martin considers Indian folklore, Buddhist and Christian mystic or anthroposophist symbols, as well as the “Spiritual Landscapes” of the North American Romanticism, quite unknown in Europe. But especially in the sanctuary of modern abstraction, in the aesthetics of the sublime, Chris Martin poaches without reservation. He allows for the Pop Art heritage to rule in this domain where things often appear ethereal. Even here, especially here, he embraces the fusion of high and low as well as the trivialization of the image. Since for the human mind to meet its borders and to shiver in humility, does it need more than a hand full of psilocybin mushrooms, those which often glisten from Martin’s paintings and a pile of good records to tune in? Chris Martin contradicts the idea that the higher the art reaches, the thinner the air gets. Where things lift off the air gets thick.

Chris Martin lives in Brooklyn, New York. He is a regular writer for The Brooklyn Rail, where he has published interviews with Brice Marden, Leon Golub, James Siena, Helmut Federle and others (www.brooklynrail.org). We show his first monographic exhibition outside the US.

Text and photos: Alexander Koch; image 2, 3, 25, 35 and 36: mickmorley

Translation: Staphanie Berger