Sep 8–Oct 21, 2012

TRAILER ON YOUTUBE

...Christopher Roth, Ornament & Verbrechen, Arno Brandlhuber, are you happy?

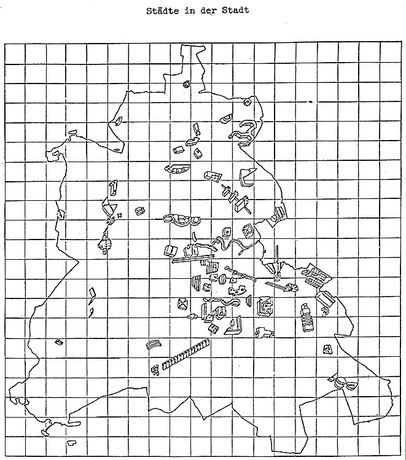

Built structures (architecture and urban planning) shape social relations, and they present an unambiguous trend: homogenization. Urban environments that used to be shared or that would have lent themselves to sharing in the future are now being subdivided into the niches of social Darwinism. Like and like congregate on urban islands clearly staggered according to income classes. In Berlin, where heterogeneity was once a defining feature of the urban fabric, it is especially evident that the reorganization of the city serves the redistribution of participation in social life: a wealthy clientele takes possession of the central areas around prestigious new residential developments, displacing to the periphery all those who cannot, or do not want to, keep upping the ante. Social archipelagos take shape, new cities within the city, all of them similarly homogeneous: the unemployed here, an arts scene there, the migrants somewhere else.

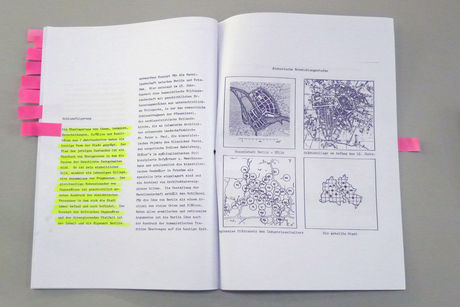

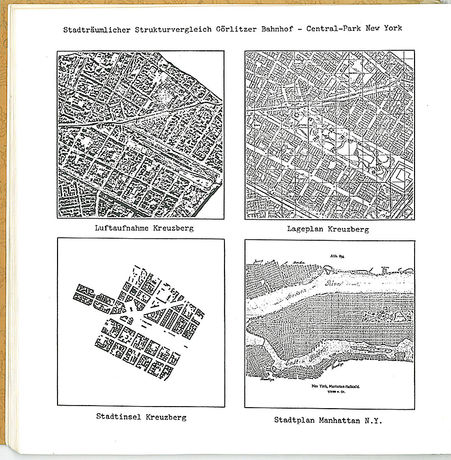

Berlin’s Mitte district is turning into a parallel society that isolates other parallel societies along its margins. Promoted and subsidized by the municipality, this development threatens to destroy the community. In his double project at KOW and the NEUER BERLINER KUNSTVEREIN (nbk), Arno Brandlhuber reflects on this process. A utopian design scheme for the city serves as a historic backdrop and point of comparison for his dystopian model describing the new Berlin: The City within the City—Berlin, the Green Urban Archipelago. The authors of this 1977 manifesto, O.M. Ungers, Rem Koolhaas, Hans Kollhoff, and others, expected that the metropolis would shrink and proposed moving the remaining population to well-functioning urban islands while greening the structurally weak spaces between them. Today, Berlin is growing, and yet islands nonetheless emerge: as a clustered structure of social demarcations. At nbk, Brandl-huber stages the consequences of letting this urban development tendency continue unchecked.

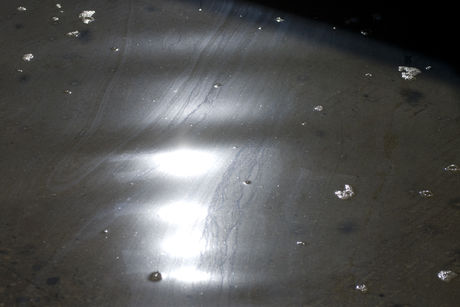

At KOW, the architect examines his own townhouse Brunnenstraße 9 in the context of this set of issues. Designed as an economic architectural and gallery model supporting heterogeneous uses, it is nonetheless itself one of those Mitte islands that reinforce social homogenization. All the building’s users (KOW, 032c magazine, Brandlhuber’s architecture studio, and an artist’s studio) are agents of the culture industry archipelago and attract their own kind. They may take a critical view of their role, but that does not change much. Three years after the gallery’s opening, Brandlhuber now revisits his architecture project with KOW to examine its accessibility and its openness to critique. He demonstratively unlocks the gallery’s doors and gates, while blocking the basement by flooding it—a throwback to the damp abandoned construction project he took over, erecting his new building on its foundations. The water disrupts all access to and use of the gallery space while also acting as a reflective surface that heightens the visual impression of the space.

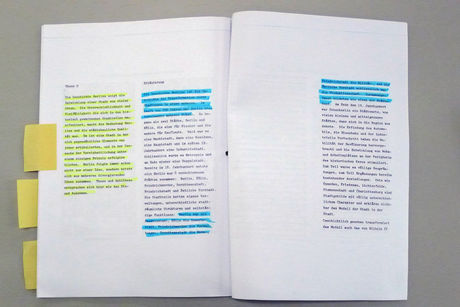

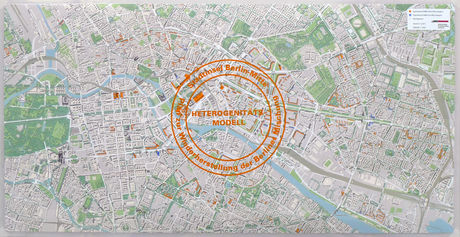

On the acoustic level, a sound piece by Mark Bain fills the basement: seismographic sensors in the structure render even the slightest reverberation audible. The building thus reproduces its resonant relation to its surroundings in its sonic interior. Brandlhuber reprints articles about real estate politics and the housing market he has collected from German dailies over the course of a year in the form of a newspaper, retracing the trajectory of the public discourse his own urban-policy demands helped shape. For comparison, the staff at KOW and Brandlhuber’s studio hold daily readings from the Green Urban Archipelago for the visitors to the gallery. The gallery team’s computer screens everyone crowds into two work islands near the entrance—show advertising clips for the upscale residential developments that now set new historic records for housing prices in Berlin. A map documenting the housing stock owned by a municipal real estate holding corporation whose rent index might guide social policies designed to counter the trend is on display in the showroom, entitled Model of Heterogeneity.

The homogenization of social relations undercuts the basis of the polity: diversity. Brandlhuber watches the redivision of the city and calls for active measures to foster its heterogeneity. His project also highlights the art world’s own tendency to form archipelagoes—rendering a debate over how everyone’s right to be part of the city can be secured in the future no easier, but certainly more urgent. We present Arno Brandlhuber as an engaged participant in discourses and cultural producer who brings his influence to bear on fields ranging from architecture and art to politics and media. His first solo project at a gallery opens on occasion of KOW’s third anniversary and is flanked by KOW ISSUE 9.

Text and photos: Alexander Koch

Translation: Gerrit Jackson

Arno Brandlhuber in conversation with Berlin based architects:

Online Reviews:

MONOPOL: DER AUSVERKAUF DER STADT

TAGESSPIEGEL: INSELN IM ARCHIPEL

ART: DER REPRESSIVE CHARAKTER VON ORCHIDEEN

Downloads: