Mar 1–Apr 19, 2014

Artists who are committed to causes are smooth operators. What they show is beautiful even when it is cruel. No matter how deeply they probe social realities that shock the conscience, the forms in which they do so please the eye. That’s not just cynicism on the part of the contemporary art world. Lending an aesthetic gloss to injustice and brazen iniquity is a prerequisite of artistic enlightenment, which needs beauty to speak of grievous ills. It’s no accident that the comedic and the grotesque are indispensable to critical forms of art (see Charlie Chaplin). It’s the foundation of their credibility that they present scandalous situations and political depravities in words and gestures that take grave matters lightly. Such artistic contortion, and occasionally mystification, does not claim that it can explain let alone improve the world, and yet sometimes it hits the nail on the head. Meanwhile, it isn’t easily captured by rational discourses and symbolic usurpation – a point to which we will return.

“A Study in Apocalyptics” is Alice Creischer’s term for the exploration of today’s predatory capitalism, which she and Andreas Siekmann conducted in 2012 and 2013. Their joint project In the Stomach of the Predators evolved in three stages – the Bergen Assembly, the Biennale Regard Benin, and the Istanbul Biennial – and each artist now enlarges on his or her findings in a solo exhibition, one at KOW and one at Galerie Barbara Weiss. Creischer and Siekmann frequently work together as artists, curators, and theorists (and in this instance, their children also play an active part), but the two shows clearly illustrate the differences between their positions, which combine closely interwoven contents with distinctive methodological approaches. So In the Stomach of the Predators is also an example of artistic collaboration: A double praxis in which we can recognize two individual voices.

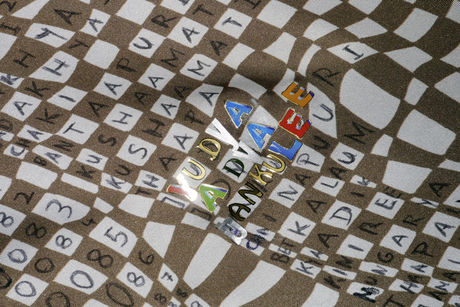

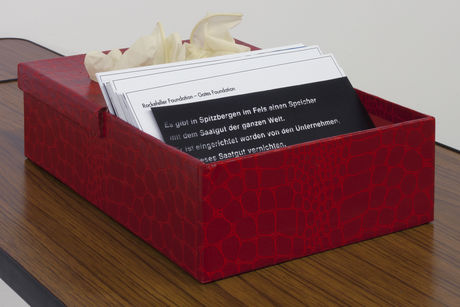

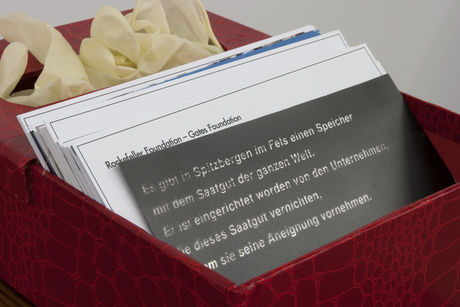

Creischer’s production picks up where her first exhibition at KOW (The Establishment of Matters of Fact, 2012) left off, returning to its structure as well as themes. Four whimsical sculptures set on tall stilts in the upstairs gallery represent predators: the wolf, the hyena, the bear, and the jackal. Each is emblematic of a different form of the privatization and monopolization of the commons and the figurehead for one of the show’s four chapters. We need to look closely to find meaning in the texts, signage, and pictorial appliqués on the animals’ clothes. There’s a precise symbolic logic behind them, but their significance is initially fairly impenetrable. Later on, in the basement gallery, we encounter index cards with statistical data and in-depth information about corporate networks and political backgrounds. They document the eviction of people from what used to be their commons to make room for the economic exploitation of their living environments by outside agents. This is toxic material, and when you touch it, you’d better wear protective gloves.

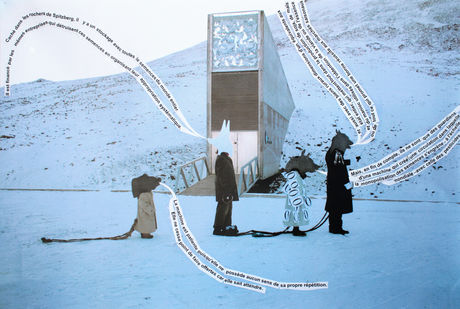

The wolf: The island of Spitsbergen is home to the secure seed bank known as Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Stored in a cavern deep in the permafrost soil is the global biodiversity of tens of thousands of agricultural crops that are being ousted as the laboratories of biotech giants like Monsanto, Pioneer, and Syngenta churn out modern high-efficiency varieties. The same corporations fund the seed bank to dispel the fear that they might be destroying the varietal diversity created by hundreds of generations of plant growth. A global gene pool, a heritage and common treasure of the world’s cultures, is effectively disappearing in the bowels of a bunker whose gates are guarded by predatory agribusinesses.

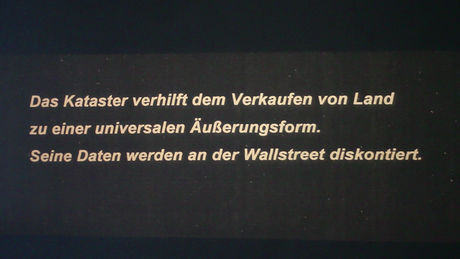

The hyena: In Benin as in other underdeveloped countries, properties are being demarcated where no such boundaries existed. Common ownership and individual rights of use were woven into local knowledge; bureaucracies now require paperwork. National authorities and investment companies survey land, determine ownership, and sell options to acres on Wall Street before the users or owners have even been expelled or compensated below fair value. The colonial partition of Africa continues, in that land is privatized for farming and building, plot by plot.

The bear: Something similar is going on in Istanbul; only the land-grabbers’ tools are different. The construction boom in the city goes hand in hand with the displacement of its people. Traditional neighborhoods such as Sulukule, the world’s oldest Romani settlement, and Tarlabaşı, the socially mixed district downhill from Gezi Park and Taksim Square, are being cleared; their residents dislodged. Members of Erdoğan’s family in government and the real estate industry work together to raze organic urban structures, liquidate public life, and develop the newly vacant urban space in public-private partnerships that yield high profit margins.

The jackal: Many predators look for new prey in resource capitalism. The exploitation of land promises greater profits than the exploitation of productive labor. Such “extractivism” literally undermines the commons, erodes living environments, and at the same time undercuts the demands for justice of the workers who populate the slums of the metropolises, a new industrial reserve army hoping for future deployments. The occupation of the commons, the expulsion of indigenous groups, and the large-scale contamination of the environment, for example by enormous surface mining ventures, were also the subjects of the final chapter in Creischer’s earlier exhibition.

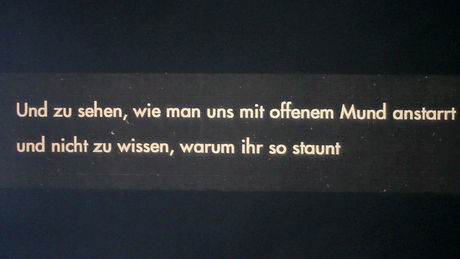

In the Stomach of the Predators delves deeper – indeed, with its index-card apparatus, it insists on imparting facts and the context in which they belong. It challenges us to read more about the complexities of the critical discourse on capitalism. But don’t we already know all these things? At least in their broad outlines? Is Creischer preaching to the converted when she rubs her audience’s noses in the dust of neoliberal emissions? None of this is going to come as a surprise to anyone who brings a sufficiently critical mind to the study of this sort of archive. But emancipation is work, the critical faculty cannot be delegated, and Creischer’s skeptical view of political statements issued by artists is distinctly palpable. She’s aware that there’s something deeply grotesque about art – you’ll expose yourself to ridicule if you seriously tilt at the windmills of predatory capitalism – and defines her position accordingly. She takes the gravity of the situation seriously, and then again, she doesn’t. She’s rightfully indignant about the greed of the wolves and hyenas, and adamant about the data that document their practices. And she rightly stages this indignation as a theater piece.

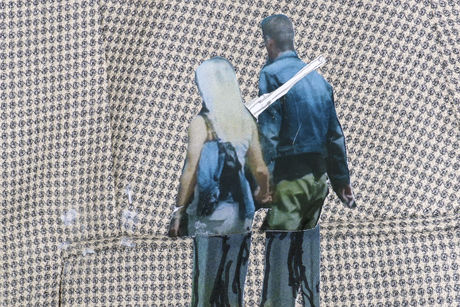

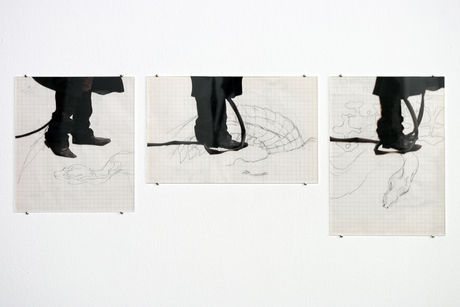

Two photographs taken during a demonstration on December 19, 2013, against the Grüne Woche, a food-industry trade fair held annually in Berlin, form a curtain behind which a film is playing. The predators are back; a sloppily dressed wolf, hyena, bear, and jackal are trotting from Spitsbergen via Benin to Istanbul. From biennial to biennial, from one political scene to the next, they are a vagabond caravan of artists or artistes of social critique, their progeny in tow. In acts of gauche satire, they appropriate the roles of predators, distributing seeds, occupying land, and lining up like beads on a string the zeroes they’ve extracted from the debasement of the commons and now hand over to the fantastic mathematics of speculation, which will turn them into ones to be added up as profit. It’s a procession of beggarly mythical creatures, dragging their hungry stomachs – ladies’ handbags containing precious objects –as prisoners drag their chains, unwaveringly waiting to knife their companions in the back at the right moment, because that’s what they are. Predators.

The scenes are real, as are the political and economic processes, and the perceived impotence of art to counter such systemic violence in any way may be no less real. If art does try (and what else is it going to do?) it’s a good idea to conceive the whole thing as a farce from the outset; and since art works often find themselves in the predators’ stomachs, they might as well be a bit indigestible. Alice Creischer has been a leading figure in the movement toward a more political art in Germany since the 1990s, and the way her exhibition uses beauty to speak of grievous ills and simultaneously hedges its bets may remind some viewers of the subversive poetics with which artists living under repressive regimes, as in the former East Germany, gummed up the censors’ dragnets. An artist who studies today’s predators as they gobble up the commons and isn’t ready to part with the common good of cultural self-determination does well not to include with her work the mining rights that might let others extract all its value.

Text: Alexander Koch

Translation: Gerrit Jackson

Editing: Kimberly Bradley

Photos: Alexander Koch