Nov 19, 2016 – Jan 29, 2017

It is a preeminent collection of the art of the twentieth century—perhaps the only one. From Marcel Duchamp to Andreas Baader and Jeff Koons, it covers almost a hundred years of cultural history, an era that has become strange to us. In the collection’s 154 items we espy glimpses of a universe of things and ideas, the forms in which that era expressed its feelings and thinking, its knowledge and visions: they are art objects and visual creations that people collectively beheld, considered, and judged. Today it takes a keen archaeological intuition to grasp how it was possible that special significance was accorded to selected objects identified as works of art. And so the exhibition at KOW is first and foremost a tribute to the life’s work of Ramon Haze. He compiled the items on display and reconstructed their forgotten meaning. His art collection—“The Cabinet”—traces several key episodes in the past evolution of art and is now regarded as the single most important source helping us to understand it.

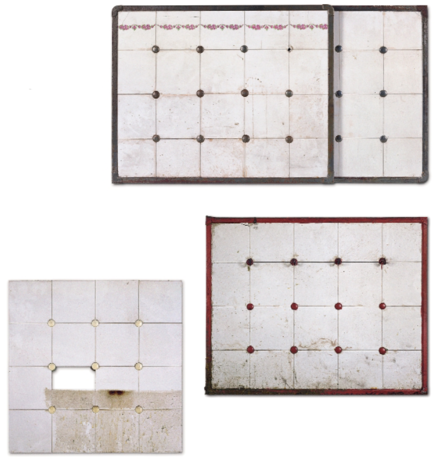

Nine “Fountains” by MARCEL DUCHAMP are the highlight in the exhibition. During a trip to Dresden in 1912, the French artist purchased ten urinals. He initially put nine of them in storage in Dresden, while one accompanied him to New York, where he tried and failed to place it in an exhibition. His piss pot, the jury wrote, was not even art. It took Duchamp a long time to win his critics over—and when he did, it was too late to finally present the other nine “Fountains.” The political situation put his storage room in Dresden beyond reach. But when the East German government tried to turn the objects into hard cash on the capitalist art market without his authorization, Duchamp beat the communists to it. In 1964, he manufactured eight replicas of the “Foundation” and sold them through his gallery. Art in the twentieth century, it seems, was always also an ideological and economic contest. In 1998, Haze unearthed the nine original urinals in a basement in Dresden. They are now in the Cabinet.

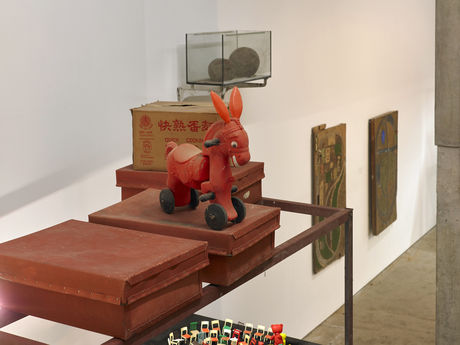

“Saltpeter” (1970–72), a set of sculptures by ANDREAS BAADER, exemplifies what political art can be. The ten electric coffee grinders in zinc buckets demonstrate the dangers of radical artists’ collectives such as Baader’s own RAF. Residues of explosives on the coffee grinders are evidence that the work was used to make bombs. But the volatile ensemble also articulates an ironic take on the RAF’s self-dramatization as a collective political bomb, underlining the self-destructive impulse at the heart of the group’s collaborative actions, which revived the Romantic tradition of unrecognized artistic genius in a theatrical gesture of grand failure. Unlike Baader, JEFF KOONS strove after fame and fortune, but in vain. Conservation of the water tanks in which two floating balls registered the minutest vibrations in the surroundings proved to be so complex that Koons’s works gradually disappeared from collections and fell into disrepair.

Closer study of the Cabinet reveals that the art of the twentieth and even the early twenty-first century drew virtually no distinction between the real and complete fabrication. People took license with the boundary between fiction and truth. Haze himself sometimes wandered off the solid ground of reality, closing his ears to some facts or even deliberately concealing them. He never disclosed many of his sources and downplayed the contributions of others; his assistants Holmer Feldmann and Andreas Grahl, for example, procured easily a hundred percent of his collection’s inventory while also creating one of the most remarkable works of art of the bygone cultural era even as the latter was in its last throes. Haze studiously avoided correctly specifying Grahl’s and Feldmann’s achievements, an omission we will seek to rectify in the following.

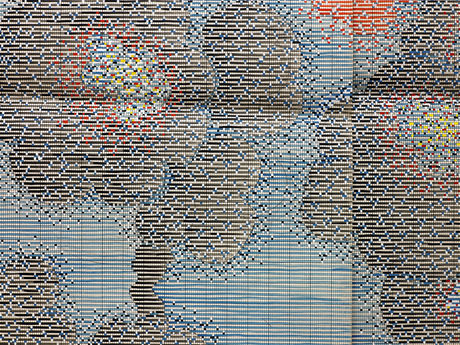

Leipzig, 1996, seven years after the fall of the Wall: the East German production of industrial, consumer, and cultural goods is no longer, and the things and ideas that furnished the world of socialism are passé. The end of an era. Rummaging through vacant apartments and shuttered factories, Holmer Feldmann and Andreas Grahl amass truckloads of urinals, toys, eggcups, glass flasks, and other finds. Following Haze’s instructions, they assemble them in an extraordinary installation: the Cabinet. They study and refine Duchamp’s recipe on how to alter the semantics of mundane objects and transform their huge pile of waste material into a gallery of modern and contemporary art. The citizens of Leipzig soon flock to the collection display at its prominent downtown location and are filled with the characteristic confusion of the post-socialist period: So what is important, what is true, and what is not? And why?

Was FERDINAND PORSCHE'S original VW Beetle, designed in 1934, art? What about RUTH TAUER'S tiles? And the sugar furnaces of PIPPIP, who was born in Chicago in 1890 and worked as a stoker on a cargo steamer? What sets the Colombian GALLARDO JUAN IBANEZ'S playpen apart from an identical playpen by the Russian ILYA KABAKOV (salvaged by Feldmann and Grahl from Kabakov’s installation “Voices behind the Door,” which was shown in Leipzig in 1996 and then scrapped)? And why did art historians for decades draw a veil of silence over EDWARD BARANOW-KNEPP'S “Machine for Changing the World for the Better,” which was probably completed as early as the 1930s? Who might be able to answer all these questions? Feldmann, Grahl, and Haze write their own version of art history at a time when the Western sense of inevitability muffles all life in the East—and play a trick on the new hegemonic style.

By sheer luck, we have a video recording of a guided tour of the collection. It documents the remarkable precision and attention to detail with which the pedagogical staff showing the cabinet conveyed Ramon Haze’s artful account of the past and pinpointed the change of values in the years after German reunification. Crucially, they did so without stoking resentments, clinging to anachronistic oppositions, or promoting fatuous conceptions of the artist’s role of the kind that would be advertised by some of the other art coming out of Leipzig. From 1996 until 1999, the art collection “Der Schrank von Ramon Haze” was probably one of the most original and substantial creative responses to the post-socialist transformation, to the revision of (art-)historical narratives and the new acquisitions policies of public museums. The latter, it should be noted, have so far not deigned to include the Cabinet in their presentations. Haze’s collection has fallen into oblivion, as has the twentieth century as a cultural era in the account it gave of itself.

Meanwhile, parts of the collection—which is now a historic artifact in its own right—survived in basements and barns in Thuringia. In 2009, we asked Holmer Feldmann and Andreas Grahl to wipe the straw off several incunables from Haze’s collection and presented them as part of KOW’s inaugural exhibition, ANTIREPRESENTATIONALISM. We have now invited Feldmann and Grahl to reassemble what is left of the Cabinet. We should add that Ramon Haze had additional collaborators: his fellow collector Pjotr Baran; Xenia Helms, Joe Kuss, Jan Wenzel, and Valentin Wetzel, who penned the outrageous descriptions of individual works (on which we drew for this press release); Markus Dreßen, who created the sumptuous design for Haze’s award-winning collection catalogue, now a rarity, and published it at Spector Books; and many, many others. Welcome to the Cabinet!

Text: Alexander Koch

Translation: Gerrit Jackson

Fotos: Martin Klindtworth / Ladislav Zajac, KOW