Mar 12–Apr 16, 2016

In the hands of certain people, pens, rulers, and showcases are as dangerous as armies. It was with quiet instruments that Europe conducted history’s greatest war of occupation: colonialism. It conquered the rest of the world with maps, museum archives, and international legal documents, the modern weaponry of bureaucracy and organizational reason. Needless to say, shots were also fired. Yet the planetary assault on “unclaimed” overseas territories was first and foremost a European administrative act. A syndicate sustaining and legitimizing the nation-state’s ascent to power, the establishment of a two-tier system enshrined in international law, and a form of official authority blind to human beings that, like any structural violence, is almost impossible to capture in images.

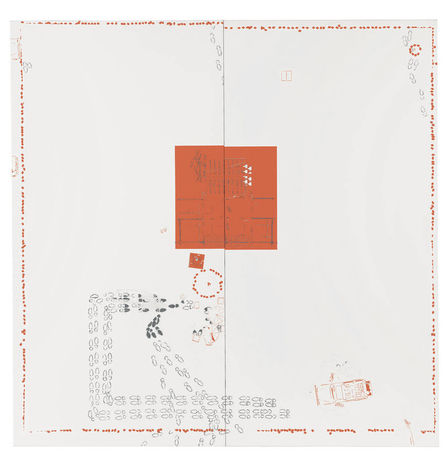

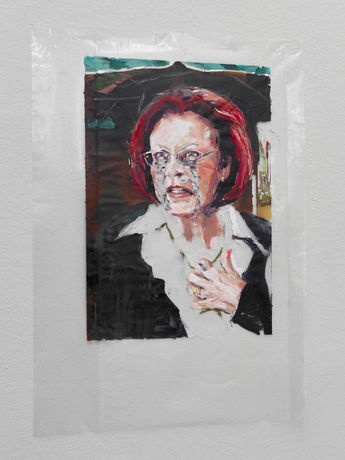

What images cannot capture sometimes becomes the subject of paintings. Working in acrylic and silicone on canvas, Dierk Schmidt has worked through the formal principles of the usurpation of the African continent that the colonial powers developed starting in the late nineteenth century. Cartography rendered the world a surface; statistics translated its inhabitants and their environment into numbers; legal codes divided people into law’s subjects and objects – all these are principles of formal abstraction that are not alien to painting, which was, after all, complicit in the project of universalism and structural rationality. Employing the symbolic registers of modern formalism, Schmidt exposes how it gave rise to new techniques of rule and government while also imprinting the resistance to these techniques upon his canvases.

In his 15-part cycle of paintings “The Division of the Earth – Tableaux on the Legal Synopsis of the Berlin Africa Conference,” created between 2005 and 2007 for documenta 12, the Berlin-based artist focusses upon two events in European-African and German-African history. The 1884–85 Africa Conference, where the continent was partitioned into economic exploitation zones, is contrasted with the lawsuit demanding reparations the Herero people filed in 2001, making the genocide that Germany committed in today’s Namibia between 1904 and 1907 a hot-button political issue. A meticulously researched and well-argued essay, by the art historian Susanne Leeb shows how Schmidt’s contemporary history painting makes legible the legal operating system that underlays the reification, elimination, and occupation of Africa’s peoples and lands. It is an operating system that lives on in today’s legal norms and trade regulations, the source code for the continuity of global inequality.

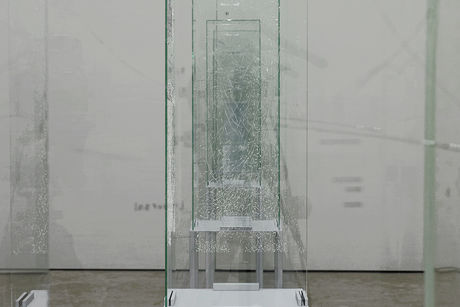

One expression of this continuity are Germany’s museum and cultural politics. In a novel gesture of dubious national sovereignty, the Federal Republic uses venues in the heart of its capital, from the Neues Museum to the thoroughly synthetic Humboldt-Forum, to stage its own past as an artifact. It harnesses artifacts of non-European history to boost the credibility of its neo-Prussian virtues. A semblance of scholarly integrity, curatorial care, and the determination to protect objects from autochthonous inadequacies serves to conceal the origins and contexts of the treasures – some threatened by potential demands for restitution – that the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation hoards in its Berlin museum empire. One popular case in point: the bust of Nefertiti, an Egyptian national symbol, is on display at the Neues Museum beneath hundreds of pounds of German conservation glass.

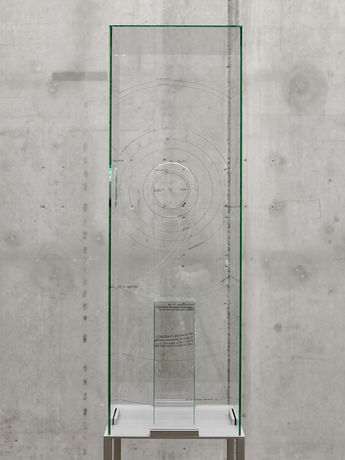

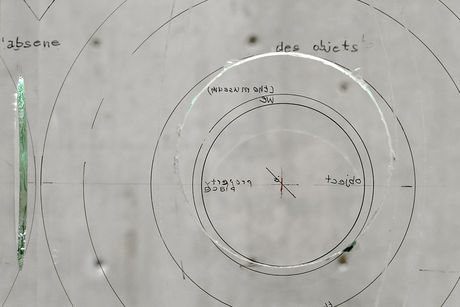

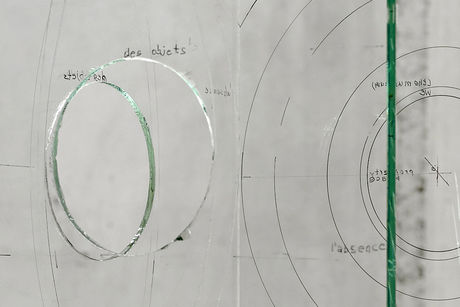

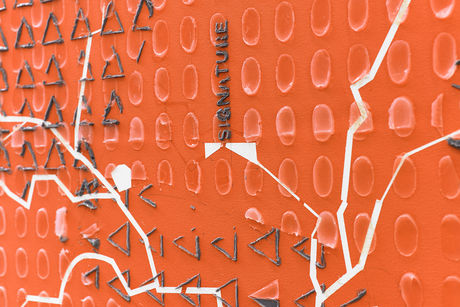

In a series of new works – paintings by other means – Dierk Schmidt uses the motif of this glass to address the visual and discursive axes that define the rhetoric of (neo)colonialism. Caught up in the gleaming surfaces of empty display cases are the thoughtless violence of appropriation and formulas for conflicting claims of ownership as well as our own position as beholders. The fragile glass plates seem to reflect the depression that befalls one in the face of the apparatus of institutional self-defense and representation. Parsing the surfaces of the theatrical illusion of transparency, Schmidt charts a delicate course between the interior and exterior of modern claims to civilizational advancement. He spotlights – and, in so doing, breaks – the barriers between governmental reason and its violence, between policy and atrocity, tracing the fine painterly line between European hubris and the ruins in its wake.

Text: Alexander Koch

Translation: Gerrit Jackson

Editing: Kimberly Bradley